The Poetry and Music of Science: Comparing Creativity in Science and Art

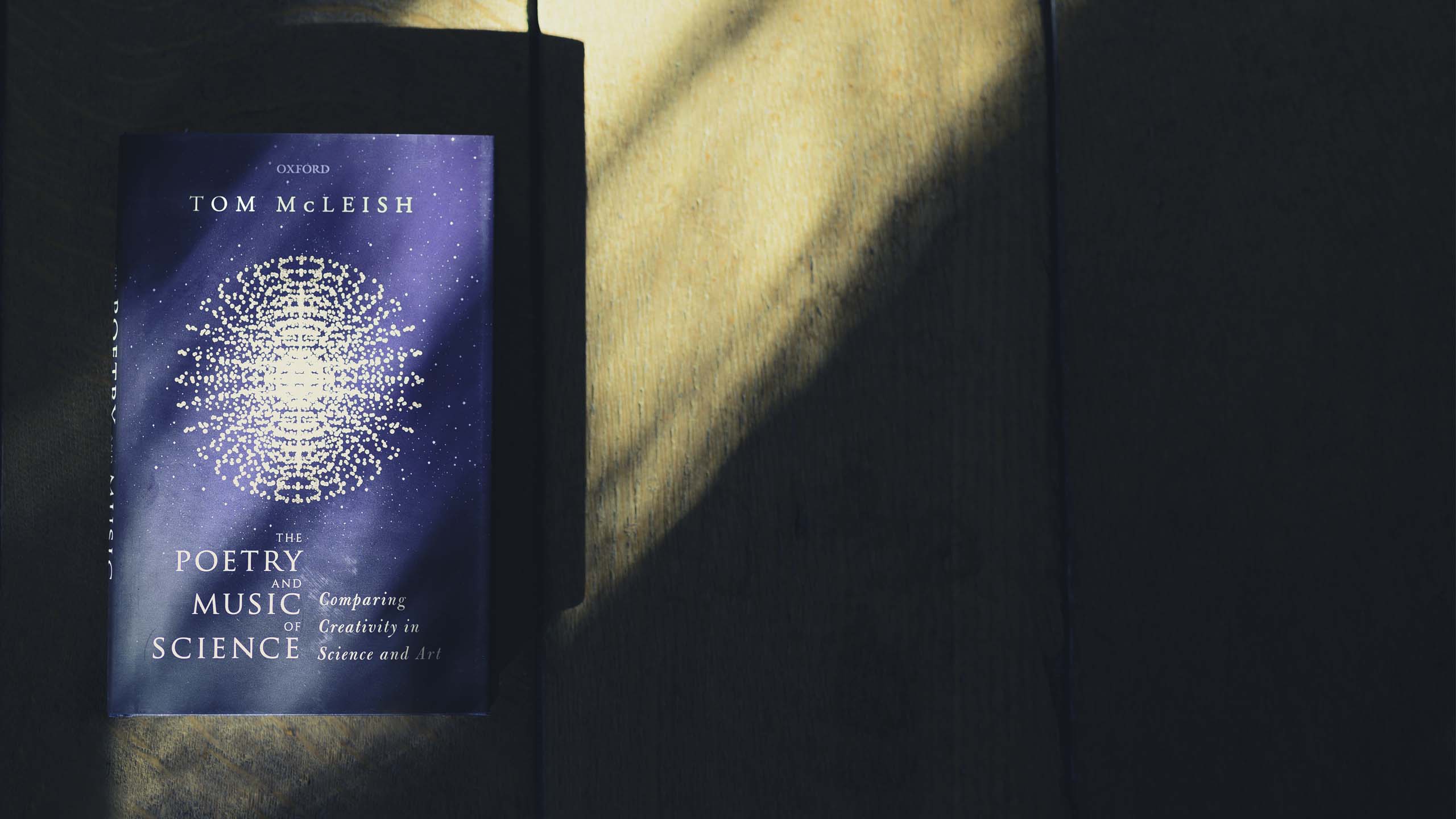

Tom McLeish is not an easy man to pigeonhole.

For 25 years this soft-matter physicist worked closely with industry, grappling with a ‘big, big problem to do with molecular engagement and entangled knotted molecules.’

Today, he can be found rubbing shoulders with medievalists in the University's King's Manor building where he spends much of his time unearthing the ‘lost synergies, connectivity and entanglements between the arts and humanities and science.’

This quest for connectivity has seen the University of York’s recently appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy traverse both the globe and the centuries in search of the ‘deep interdisciplinarity’ that links what the scientist and novelist CP Snow famously identified as ‘the two cultures’ in his 1959 book of the same title.

The result is a magisterial riposte to Snow, The Poetry and Music of Science: Comparing Creativity in Science and Art, that explores the three creative endeavours of music, painting and poetry to expose the hidden imaginative roots that entwine science and art.

He likes to think of this new work as his ‘not the two-cultures book’ since it shows, in opposition to Snow, how anyone who creates, be it with music or mathematics, oil paint or quantum theory, is engaged in both ‘the imaginative interpretation of the world’ and ‘the rigour of form’ that are the prerequisites of making science and art ‘fit for purpose.’

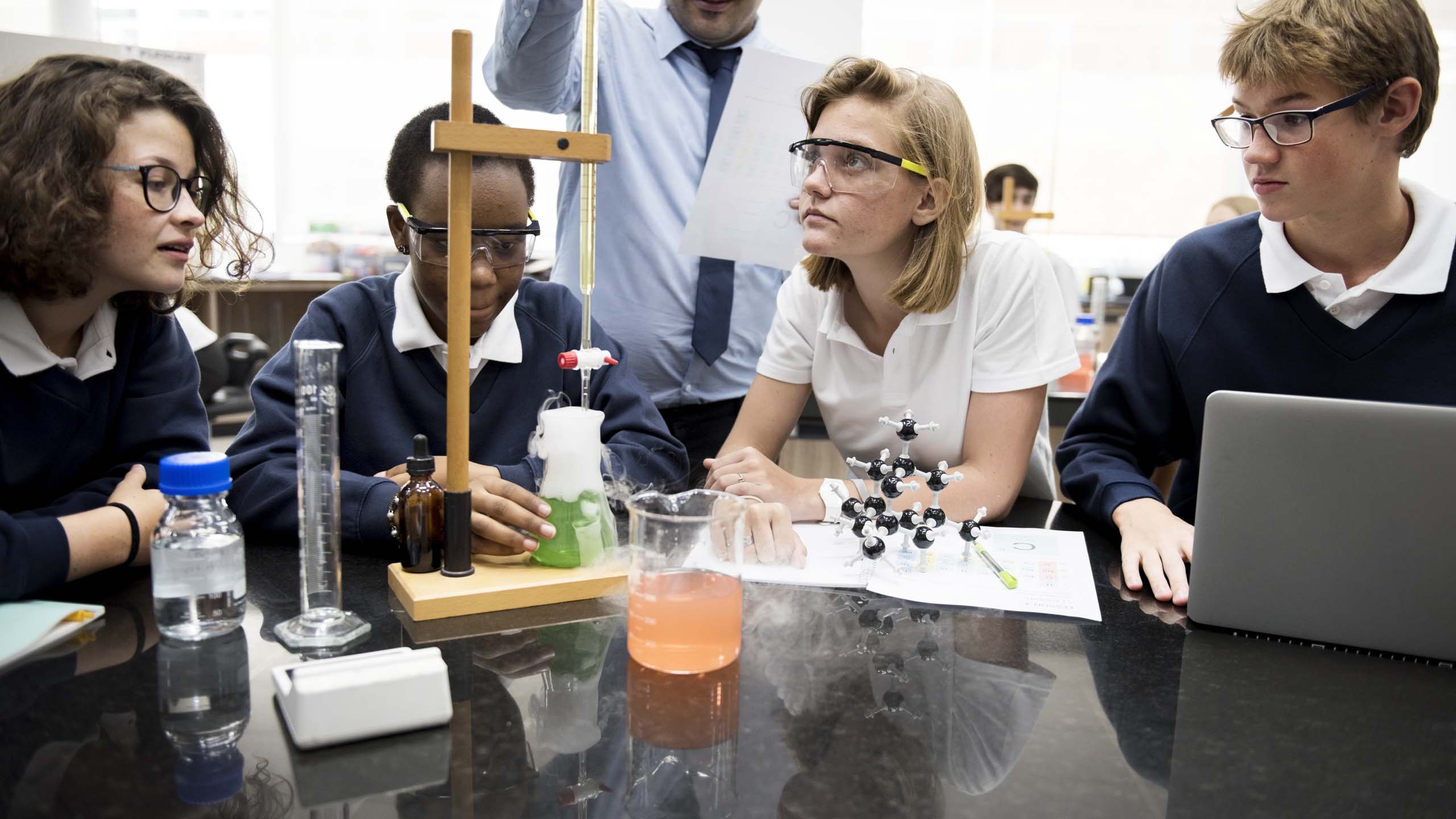

So, how have we lost sight of this connection? For Professor McLeish, a good deal of the answer can be seen in our approach to mainstream science education.

“The message I kept getting from bright, articulate sixth-form pupils was that they had lost interest in science because they thought that it had no role for their imagination and creativity.

“I don’t want to stop young people choosing the arts and humanities; on the contrary. But, if their reason is that we have given them the impression that science is all about regurgitating facts and has no role for creativity, then we are doing young people a huge disservice.”

But he believes the tide is turning.

“My own position here at York is a strategic intent to build collaborations between the sciences and the humanities, and has been extraordinarily fruitful in its first year alone. There is a clear desire among students to explore the connectivity between domains of academic knowledge and York is a very natural place to do this kind of work. It feeds a richer imagination that is so important, given the big global challenges we face,” he adds.

On the wider stage, the rise of Institutes of Advanced Studies in the USA and Europe, from Notre Dame Indiana to Durham in the UK and Odense in Denmark, is seen by Professor McLeish as a sign of ‘little flowers blooming through the concrete’ as scientific and humanities researchers engage in multi-disciplinary programmes.

He is not, however, advocating that researchers abandon core disciplines in an attempt to become experts in three or four fields. On the contrary, the challenge is to become deeply expert in one field while learning how to connect and communicate with others, known in the recruitment environment as ‘T-shaped skills.’ These ‘T-shaped academics’ have deep domain knowledge – “they have to have something worthwhile to bring to the collaborative party” – but also want to expand the bandwidth of their communication by engaging with others whose work complements their own.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that he has been working closely with the University’s seven Research Champions who he sees as key to fostering this collaborative culture.

“It’s great that people can focus on their own discipline, but there are also these T-shaped people who are intrigued by the idea of branching out to explore other connections. Once they have tasted it, they come to love it.”

He also recognises that some, especially early career researchers, might see this approach as high-risk.

“If you go about it in the wrong way, that can be true. But in the right way, the opposite is the case.

“This was beautifully articulated to me the other day by a graduate student who told me that, when she attends a conference or workshop in her own discipline, she finds it difficult to speak up and give an opinion in a room full of people with so much more experience than her. In a more interdisciplinary setting, by contrast, even wizened professors are like undergraduates in all but their own disciplines: so it is a wonderful equaliser, and she felt less daunted and able to speak up.”

Further signs of flowers blooming through the concrete will be seen at this year’s York Festival of Ideas which features a full day based around the three key themes in his book – the visual, the textual and the abstract – with panellists who are experts in the fields of science, art, literature and music.

“It’s going to be a fascinating event. One of the things I discovered researching the book is that while scientists can be shy about their experiences of imagination, the artists, writers and composers I spoke to also needed the same patience – and similarly the occasional drink – to draw them out on their need to experiment.

“Without making the naïve claim that art and science are in any sense ‘doing the same thing’, the similarities in the experience of those who work with them are remarkable.

“They need digging out because they become obscured by scientists shy of talking about imagination and artists about experiment. The Festival of Ideas will provide a day of fertile digging. Who knows what future blooms we may plant.”

As part of the University of York’s Festival of Ideas 2019, Professor Tom McLeish introduces The Poetry of Music and Science, a day of events to challenge the assumption that science is less creative than art, and find common territory in the creative process.

This free event will be held at the Tempest Anderson Hall, Yorkshire Museum, Museum Gardens, York on 16 June from 11am to 5pm.

www.yorkfestivalofideas.com