Disability Pride Month at the University of York

July 2022

About Disability Pride Month

Disability Pride Month takes place each July. It’s a time when disabled people and allies celebrate disability as a positive identity and culture, and also challenge systemic ableism, discrimination and marginalisation. Disability is complex, so disability pride will mean something different to each disabled person. Accepting a disability, neurodivergence or chronic illness is an ongoing journey, and everyone will be at different points. In a general sense, Disability Pride Month is a time for disabled people to celebrate whatever stage they’re at, and non-disabled people to reflect on the fact that disability isn’t an inherently negative thing, but rather simply a fact of life.

The profiles below are the stories and experiences of some of the disabled students and staff at York. They reflect both positive and negative aspects of life as a disabled person, and we encourage you to watch, read, and reflect

The Disability Pride Month flag

The Disability Pride Month flag

I’m Sophie, a second year history student and the intern behind this project. As a disabled person, Disability Pride Month is one of my favourite times of year; it’s a time to feel proud of my disabled identity, even when society can be so determined to make it feel negative. I wanted to showcase some of the incredible disabled people who are studying and working here at York, and all their stories.

If you’re disabled too, I hope you see that there are peers and role models for you within our community. If you’re non-disabled, I hope you take the time to listen, learn, and reflect - each of these interviews has a section discussing what we wish non-disabled people knew or did, so take it on board!

Joey McNamara

(he/they pronouns)

Joey is neurodivergent, and an Employer Engagement and Events Assistant in Careers and Placements. In this video, he discusses his experiences of getting good work-life balance and self-advocating for his needs, what disability pride means to him, and the ways that non-disabled people can support disabled people, in the workplace and beyond.

Tara Course

(she/they pronouns)

I've been here for five years. I'm currently finishing my Master's degree in Environmental Science and Management, where I'm the course rep as well. Alongside that, I work for Alcuin College as a College Life Advisor, so I’m both staff and student.

I've got a couple of different disabilities. I broke my back when I was 17 and struggle with lasting chronic pain and mobility issues from that. I’m also diagnosed with hypermobility, so sometimes my joints don't quite do what they're meant to do, which has made my degree quite interesting, because staying on my feet can be quite difficult. And then I've been struggling with my mental health since I was about 12, so I’m an advocate for mental health and understanding around that.

How does your disability affect your work or your life?

I think it changes every day. You'll probably get this from anyone you speak to who has issues with chronic pain and chronic fatigue, but trying to get people to understand that you are always in pain is really interesting.

Whereas people who don't struggle with that might slip and trip and really hurt their knee one day, and that's the worst pain they feel all day, that's a general five for me - just my normal working life. And then some days everything goes a bit wrong and you wake up and you're in so much pain that you can't really move. Being a student that does a quite physical degree has had its challenges in the past, and has meant that at some points I've had to ring my lecturers and say that I can't come on this field trip cause I can't physically get into campus. Generally they've been really good about it though.

I'm quite lucky in that I work at a desk job at the minute, so I can do my work from home if I need to. But I can also sit and not have to run around after people, which is a difference from working hospitality like I used to. It's definitely interesting trying to explain it to non-disabled people; that you are never not in pain, just some days are better than others.

What does disability pride mean to you?

I think it's really important. I spent years trying to convince myself that I wasn't disabled, especially because where I grew up, there was so much stigma around the word disabled and disability. I was diagnosed with my joint issues when I was a baby, and then breaking my back kind of exacerbated a lot of that for me. It was only really when I got to university that I started to accept disabled as a label. Disability pride is something that I've become okay with and had to teach myself, but if we can push it more now then people that are growing up in similar circumstances to how I did aren't gonna feel so ashamed. It's taken me so long to accept, and there's been so many resources I could have accessed as a child as well - I could have been so much better at my exams if I just acknowledged it earlier on.

I think internalised ableism is a thing that so many disabled people have. People with some form of disability, whether it be mental or physical or hidden or invisible, struggle with ableism anyway, but the internal voice is often quite a lot louder. Getting used to that and accepting it in myself was a bit of a journey. I don't care now if people call me disabled - I call myself disabled. And if people like us can go out and do what we do, which is so much harder than anyone who's non-disabled, hopefully the more that's in the public eye, the more it becomes a normal thing, then the fewer people are gonna grow up feeling ashamed of themselves and their own limits.

What do you wish non-disabled people knew about being disabled and Disability Pride?

Just having a little bit more patience is really key. Many of the issues that I have come with a lot of things like brain fog and being a bit slower. Sometimes I really struggle to hear people, and then get people getting really angry at you, because they think you're staring. But I'm lipreading - it's not rude, I just can't hear you if I don't lipread because the words don't quite go right in the sentence! Having that bit of patience before deciding that someone is being slow, or if your email hasn't got a reply straight away is really important.

You don't know what everyone's dealing with, but also ask rather than assuming. I don't use mobility aid, but sometimes I limp quite badly - it's normally that my hips or my knees have dislocated and I'm in pain - often people make some form of really off-colour joke or assume things. If you're not sure, generally we’re nice people, ask us about it, instead of sitting there thinking we’re lazy or trying to get out of things. Just have a conversation with us - I'll give anyone all the time in the world to talk about disability and all of the resources that I know if you wanna learn about it, but I can't do that if I don't know that you’re interested! The support from non-disabled people, to people who are struggling is really, really important. Even if you're not impacted directly by other people's disabilities now, it doesn't mean you won't be at some point in your life, so be a bit nice to people.

Chloe Turner

(she/her pronouns)

Chloe is a postgraduate student, currently studying an MA in Poetry and Poetics, and about to start a PhD in English with Creative Writing. In this video, she discusses her experiences as a student living with Fibromyalgia and Bilateral Hip Dysplasia, her thoughts on Disability Pride, and the real impact of a seemingly hidden disability on her day-to-day life.

Ash Allison

(xe/xem pronouns)

Ash is an undergraduate student studying Archaeology whilst living with multiple disabilities that affect both xyr physical and mental health. In this video, xe talks about their experiences with accessing education and healthcare, and living with multiple conditions.

Julia Sarju

(she/her pronouns)

Julia is a lecturer in the Department of Chemistry who researches chemistry education, as well as the departmental disability lead. In this video, she discusses her journey to accepting her disability, from childhood to now, and her experiences as a disabled academic.

About the Medical and Social Models of Disability

Something I wanted to talk about here was the medical and social models of disability, which you might have heard referenced in some interviews. They are different ways of conceptualising and understanding disability within society. For many disabled people, myself included, the social model of disability is very empowering - my disability can never be cured or completely healed, but under the social model, society can still make adjustments to ensure my needs are met.

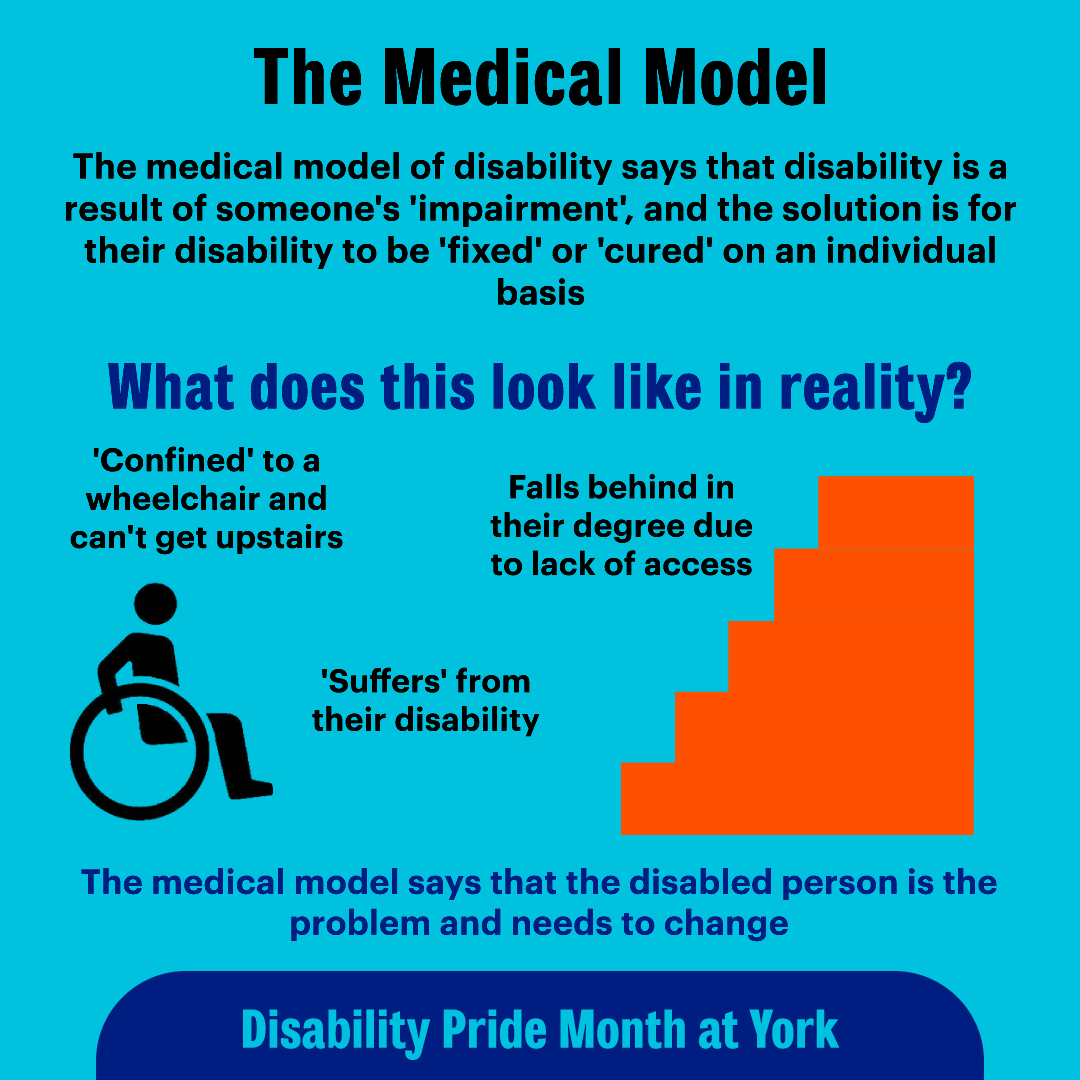

The medical model of disability says that someone is disabled by their impairments. As such, these impairments should be fixed, treated, or cured, by individual medical treatments - even if they aren’t causing any pain. If it cannot be cured, the medical model says that there’s just not much to be done, leading to individuals being isolated and excluded from society. This model focuses on an individual’s impairment - what’s ‘wrong’ with them, instead of what society could do to support them. The negative framing of disability provided by the medical model of disability can affect how disabled people feel about themselves. If you are told by society that your body is the problem, why would you ever challenge systemic discrimination and exclusion?

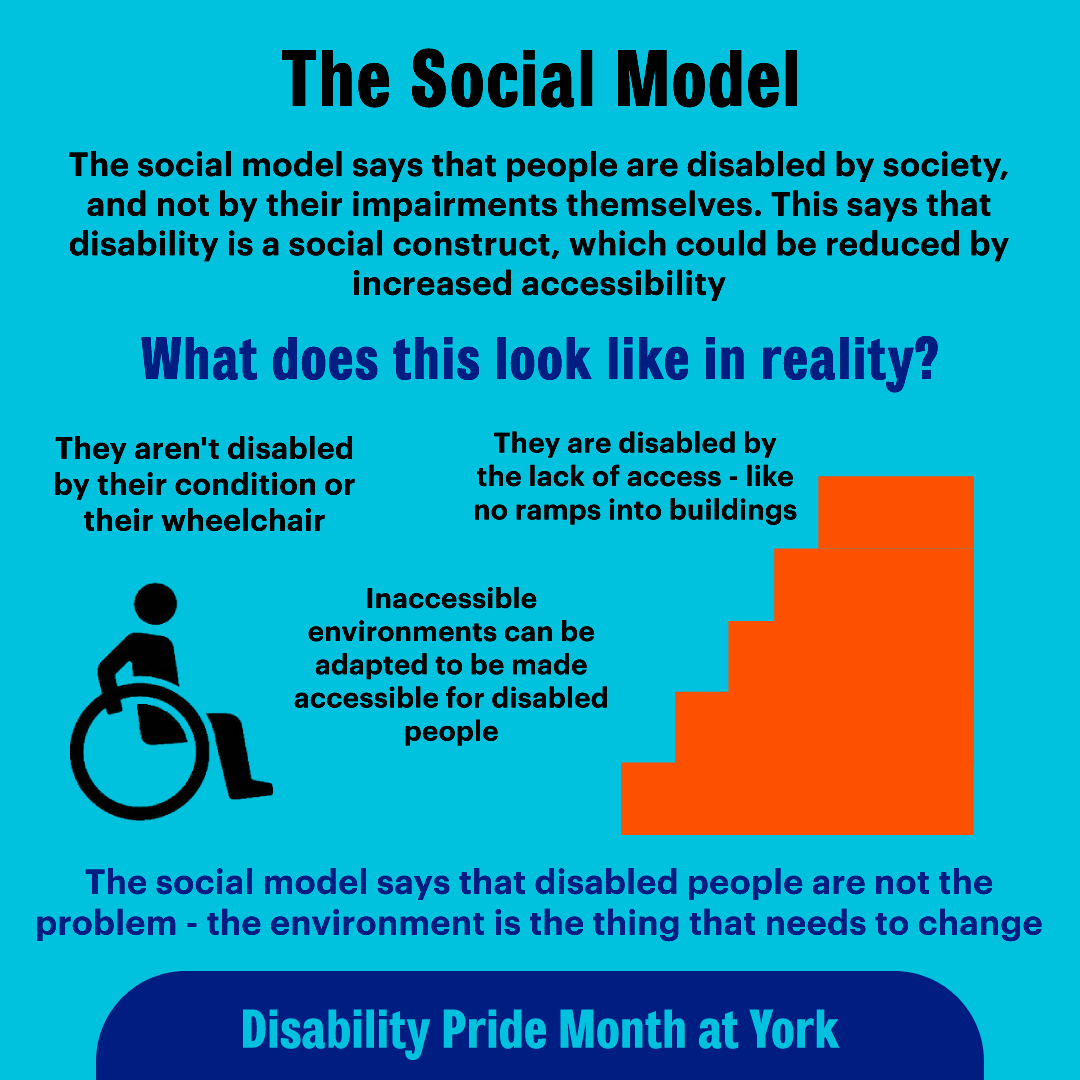

The social model of disability was developed by disabled people in the 1970s to better frame their experiences. It says that disabled people are not disabled by their impairments or their bodies, but by inaccessibility in society. Therefore, disabled people are not the problem and do not need to be cured, but rather the environment needs to change. The social model identifies lots of different barriers within society including: the physical environment, people’s attitudes, how institutions and organisations are run, and how people communicate.

To give a real world example: John is a wheelchair user who attends university. He cannot access the library, and some other buildings, because they are not wheelchair accessible. This is causing him to fall behind in his work, as he cannot access the course teaching or materials to the same level as his peers.

Under the medical model, John’s disability is the problem. He is impaired by his own body, and if this cannot be cured, there is nothing else that can be done.

Under the social model, the problem is that the buildings are not accessible to John, and no alternative arrangements have been made. He is disabled by this, rather than by his body. The solution is to make the buildings wheelchair accessible, or provide an alternative way for John to access his course - for example, his classes could be moved downstairs in a building that doesn’t have a lift, and library books could be scanned for him or collected by another person.

The social model isn’t perfect by any means - no amount of adjustments can cure chronic pain - but understanding disability in this way helps disabled people to feel empowered, and to be better included in society. For these reasons, it's widely accepted as the better model.

Reflections and final thoughts

Disability Pride Month takes place every July, but that doesn’t mean you can stop thinking about disability for the rest of the year! I think these interviews have been really insightful, and have left us all with a lot to think about and reflect upon. No matter your role or position - disabled or not, staff or student - being aware of disability issues is really important, and allyship is truly appreciated.

I wanted to finish up with some things to think about further. Here are a few parts of the interviews that I thought were really poignant, or things that I’ve always wanted to tell non-disabled people.

Julia discusses the proportion of students and staff declaring disability in higher education, and the impact this has on individuals and academia as a whole. I found these statistics really shocking!

I really liked this point from Tara about how disability pride has shaped her experiences as an adult, in contrast to her childhood - it really resonated with me!

And finally, Chloe talking about the reality of living with chronic pain. As someone who also has chronic pain, I wish everyone in my life knew this and respected it!

Staff, students and visitors who would like to access advice and support at the University of York can contact Disability Services via our website.