"What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others"

- Pericles

The Legacy Newsletter | Edition 16, June 2025, The University of York

Welcome to the June edition of the Legacy newsletter.

“What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.”

These powerful words by Pericles perfectly capture the essence of true legacy: one created through personal connections, kindness, and the ripple effect of our actions.

Inside this edition, we're honoured to introduce two University of York scholarship holders who share their personal stories of how the kindness of others didn't just offer financial aid, but opened doors to new opportunities and transformed their journeys here at York.

“I carry with me a deep sense of gratitude - to the University of York, to my family and friends, to the donors who provided the scholarship, and to everyone who has supported my journey. Every lecture I attend, every opportunity I embrace, is made possible by the generosity and belief of others.”

This edition is a little longer than usual as we feature three alumni friends who graduated in 1966/67 and went on to have successful writing careers: Diana Reynolds Roome, Nigel Fountain and Amanda Sebestyen. They each share vivid memories of their time at York and the people and experiences that made a lasting difference in their lives. You'll also learn about gifts of artworks and important archive material.

These thoughtful contributions join recent legacy gifts to the University, such as £100 book tokens for English Literature students, a £1 million legacy to support bursaries and scholarships for our most vulnerable students, a collection of jazz records for research purposes, and a £500 gift to support mature students. As these examples show, all legacy gifts, no matter how big or small, make a meaningful and lasting difference to our students and researchers.

Including the University of York in your will offers a remarkable chance to weave your values and, perhaps even a tribute to the friendships that have enriched your own life, into the very future of education, research, and our community. Your gift won't just be a donation; it will become a lasting part of the University's fabric, actively empowering generations of students and researchers.

To discuss leaving a legacy gift to York, please email me at Maresa Bailey or call me on 07385 976145.

Maresa Bailey, Legacy Manager

Diana Reynolds Roome

English Literature and Music, 1967

I credit Timon of Athens with getting me into the University of York. I had my sights set elsewhere, but York’s invitation to an interview arrived first. The possibility of studying music as well as English was immediately enchanting, as I’d never heard of a combined-subject degree – an innovation at that time.

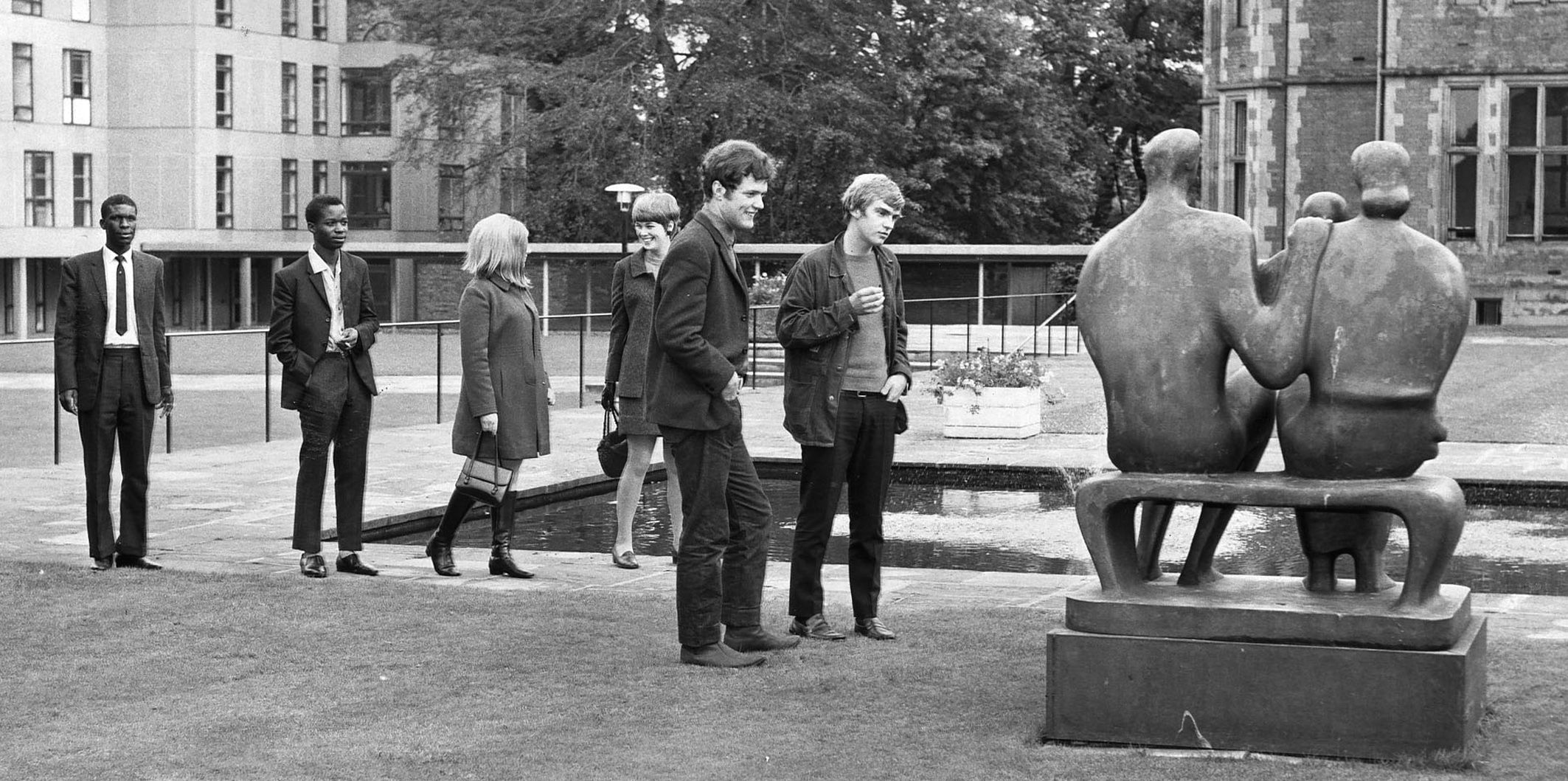

Heslington Hall, where I was summoned in late November 1963, stood in splendid isolation on the edge of the village, with barely any sign of a campus – just green fields, manicured trees and a Henry Moore sculpture. Professor Philip Brockbank was head of the new English department, and during the interview, he started quoting from Timon of Athens: “My long sickness of health and living now begins to mend.” To my surprise, I heard myself finishing the line: “… and nothing brings me all things.” Brockbank looked interested too, as that play was not typically part of a schoolgirl’s curriculum. My lone attempt to understand it had been a failure, but the striking paradoxes in that line had made a deep impression.

The inaugural year of the university had just begun, and though there were only about 200 students then, excitement was palpable. That week was memorable for grimmer reasons too. Watching TV news while staying with a great-aunt who lived in Malton, the wider world came crashing in with Walter Cronkite’s stunning announcement that president J.F. Kennedy was dead.

By Christmas, I’d been offered a place in the English and Music departments (though the latter did not yet quite exist) for the following year, 1964. York at that time seemed daringly far from my home in a small market town in Buckinghamshire, more than 200 miles away. But I accepted the offer without hesitation. My parents had not allowed my sister, older by four years, to take up the university places she was offered. My father couldn’t see the point of higher education for girls, which he associated with charmless females who put men off by thinking too much. He was also worried about the costs, though tuition wasn’t even an issue (and it remained gloriously free for many years). Luckily, my mother was almost as excited as I was, so I seized my chance.

With almost a year to go before I could start, I taught, then landed a job as a guide at the Shakespeare Birthplace in Stratford-on-Avon. By chance that summer, Timon of Athens was playing at the Memorial Theatre, and I heard Paul Scofield’s sonorous delivery of the line that may have landed me my place at York.

My first year was almost entirely centered on Kings Manor near Bootham Bar, smack in the middle of York. I was star-struck by the beauty of the building, the freedom of my days, the excitement of the curriculums, and the excellent quality of food in the gracious dining room just up the steps from the Kings Manor courtyard.

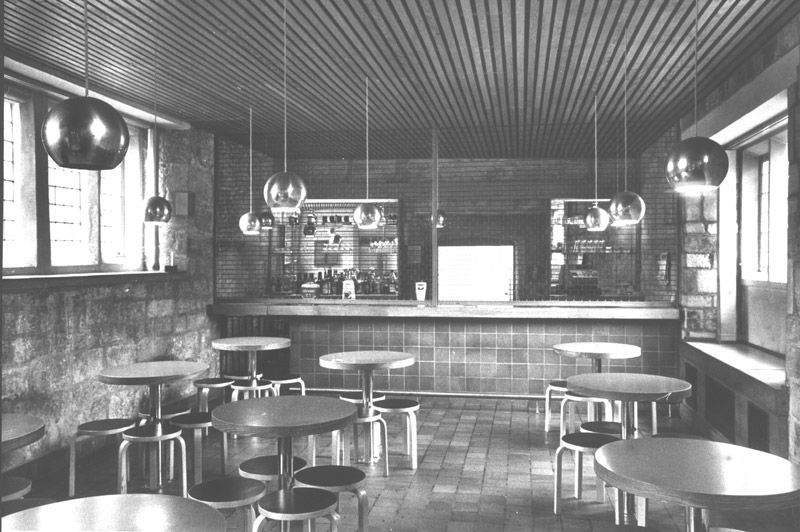

Everything was new, and the Common Room, approached up another grand, ancient stone stairway, was furnished with strikingly “mod” orange easy chairs. At the bottom of the stairs was a bar, which seemed highly sophisticated and faintly wicked. On Saturday evenings, there would be a “rave-up” in King Henry VIII’s wine cellars, which lay beneath the modern brick offices where lecturers held their tutorials. We bopped exuberantly to Twist and Shout, but I recall minimal alcohol, no drugs and never any unruly behaviour. Or maybe I just failed to notice. I did, after all, practice singing Faure’s fey love songs in those same cellars with a piano on Sunday afternoons.

My digs down the road off Bootham were distinctly less glamorous, with a landlady who scolded and charged for each piece of Ryvita I devoured when I came in - not very late but always ravenous. Two other students who had started the previous year had rooms in the same semi-detached terrace house. One, who studied English like me, has remained a friend to this day, as have several others from those first two bountiful pioneer years.

Several times a week, I walked over Lendal Bridge and up the hill to Micklegate. The Music Department consisted of a few small rooms and three teachers. Professor Wilfred Mellers was formidable, pacing up and down the classroom as he explained to a handful of students that the tritone (or augmented fourth) was banned by the Pope in 1399 because it was considered representative of the devil. How could I ever forget?

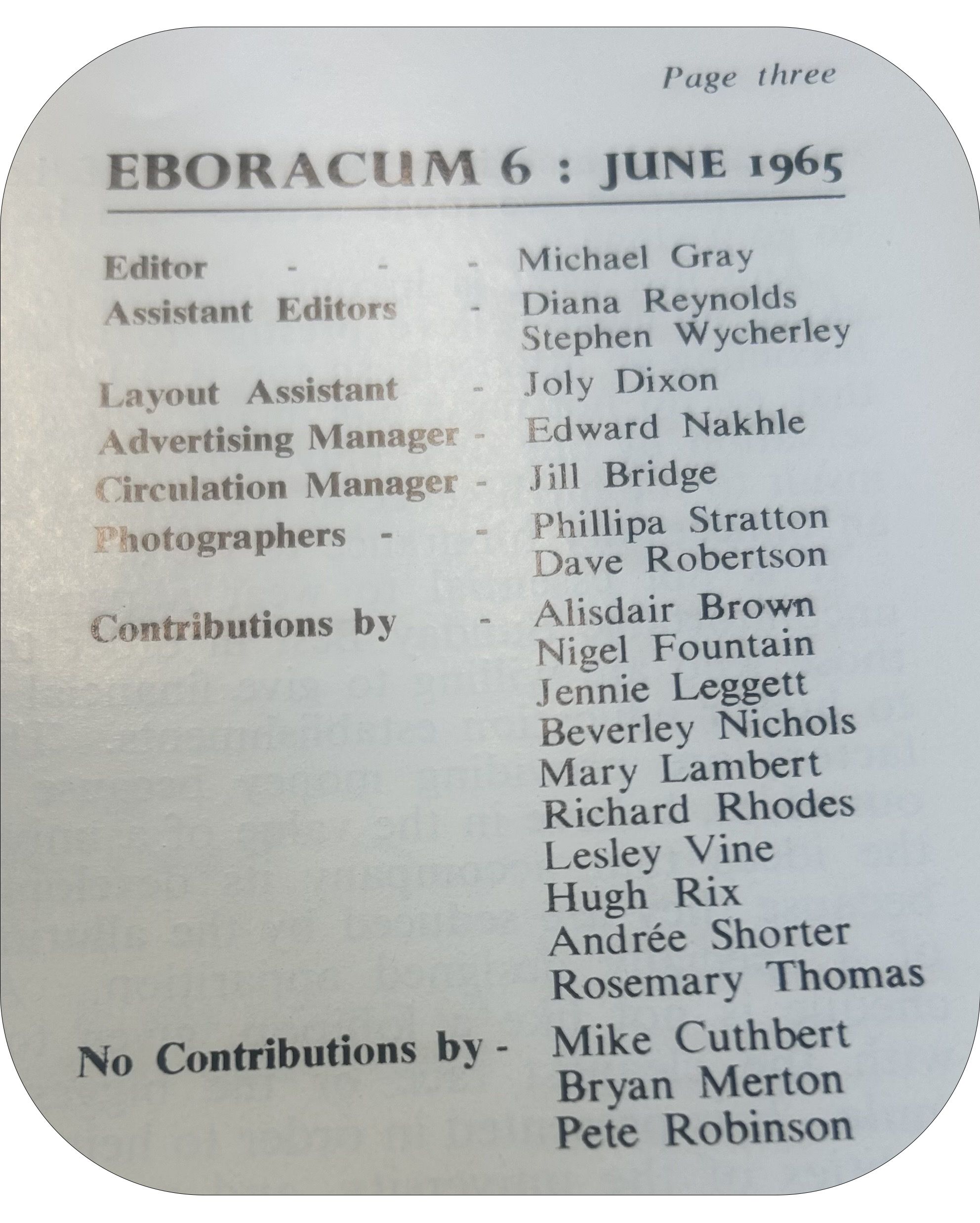

I quickly became involved in journalism, writing and editing for Eboracum, the first student magazine with a distinctly artsy flavour. Nouse soon followed – newsier, scrappier, and more popular. I was excited to review plays at Theatre Royal and local art exhibitions, also to sing in a choir that got serious reviews in the city newspaper. Words and music were my passions since I was very young, and I sang as I penned poems and stories.

Most of the people I knew were studying English or History, as many standard degree subjects did not yet exist at York. Those taking social sciences, politics and economics were based at Heslington, where a campus was slowly rising into three dimensions. I belonged to Langwith College, but that didn’t mean much as I seldom went to Heslington, except to access the new library and for special events. Though there were only around 500 students in my first year, I felt overwhelmed by the crowds and found it difficult to socialize for more than a short time without inadvertently tuning out. I was preternaturally shy and unused to talking, either socially or in seminars and tutorials. The small, Christian all-girls boarding school I’d attended did not encourage discussion and had no expectation that their pupils might progress to a university. So in the presence of my male tutors at York, I was reduced almost to frozen silence. I encountered only two female lecturers at York and rarely saw them.

When I was preparing for university entrance, I did have one brief experience of a male teacher - a Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, close to retirement, who offered to give me a couple of tutoring sessions. Hugo Dyson had been a member of the Inkwell Group, a friend of C.S. Lewis and J.R. Tolkein. He was a charming and gentle guide, and after I came to York he wrote me a few letters. His script was so hieroglyphic (or one might say donnish) that I could barely decipher what he wrote but I kept the letters.

In one of them he told me that he'd left his entire library of 17th and 18th century writings, including many first editions, to the U. (See Dyson Collection.) I have never seen it, but hope to have the letters he wrote to me join the archive.

In my second year, I rented a tiny flat in Stonegate where I retreated often to seek solitude. It cost two pounds five shillings a week and I could only afford two pounds, so I took a job at Banks Music shop just opposite, adding up their sales of records and sheet music for the day with a pencil. Eventually I was able to buy a secondhand radiogram of exquisite tone, and a boxed double-record set of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, which I played at high volume above the cobbles of Stonegate. Just behind my flat lived an elderly vocal coach who claimed to have given the marvellous mezzo-soprano Janet Baker her first lessons. Under his instruction, I practiced vocal exercises as York Minster’s bells chimed sonorously, marking the times of day. In my final year, living in Fairfax House, I worked on a long essay about early twentieth century English song writers who based their work on English folk song and poetry – though Professor Wilfred Mellers clearly did not think this a sufficiently challenging subject.

The question of a career loomed, but female journalists were the exception in 1967 and mostly relegated to Women’s Pages. The National Book League gave me my first postgrad job, as a researcher; later I went into educational (ESL) publishing. But despite my privileged education, I felt crushed by my ignorance of the world. My remedy was to travel overland to India, relinquishing my return ticket to teach English in a chaotic school in the Kathmandu Valley. That experience broke open my perspectives, and in a narrower sense showed me what I needed to learn. So, on return to England, I enrolled in a Cert. Ed. course at Oxford. Teaching practice at Roedean on the Sussex coast yielded a plum opportunity to teach literature there. I turned it down to venture into another unknown territory, the industrial Midlands, to teach ESL to recently arrived immigrant children and women. Returning to London later, I was afforded the sheer delight of creating flimsy magazines for European students of English, then took the plunge and started writing freelance articles for a wide range of publications, including the Guardian. Eventually, a full-time job as a feature writer won me a writer of the year award from IPC.

A 1980 trip to California to visit my sister and research some articles was prelude to another upheaval. Suddenly, I was living in Silicon Valley (near San Francisco) with my husband Charles, then two glorious and funny boys. It was a struggle to re-establish myself in this profoundly different culture, but eventually, my articles started appearing in a range of US as well as British publications, focusing on health, social issues and the arts. I later became editor for the Stanford School of Business. My children’s books (published in the US and UK) gave me a fantasy life to counterbalance the practical one. Now I’m writing a memoir of my travels to India and Nepal more than fifty years ago – a learning experience that beat even the Universty of York.

Information on Leaving a Bequest from the USA

The University of York in America is an organisation exempt from taxes under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. (EIN number: 30-0241333). Any bequests to the University of York in America are tax deductible.

The Henry Moore sculpture outside of Heslington Hall in 1967

The Henry Moore sculpture outside of Heslington Hall in 1967

King's Manor 1960s

King's Manor 1960s

Cellars Bar, Kings Manor 1960s

Cellars Bar, Kings Manor 1960s

Professor Wilfred Mellors, 1965

Professor Wilfred Mellors, 1965

Contributors, Eboracum 6, June 1965

Contributors, Eboracum 6, June 1965

Diana Reynolds Roome, Fairfax House 1967

Diana Reynolds Roome, Fairfax House 1967

Amanda Sebestyen, Heslington Circle Member

English, 1967

The first person I ever met at the University of York was Dr Bernard Harris, who interviewed me early in 1964. We started a wonderful conversation which continued for three years and more.

As I was leaving Heslington Hall - that exciting mix of sensitive restoration and 1960s modernism - I was fascinated to see undergraduates heading for their teas. A tiny vibrant woman with a ringing laugh (later known to me as Haleh Afshar, who I was proud to call my friend) and a tall Bohemian-looking man with sideburns (Roger Hill, who I never met apart from his starry friend John Fry) both stood out. I was thrilled but slightly intimidated.

Bernard Harris was a lifeline as well as an intellectual treasury for lots of us in the English department, but particularly for young proto-feminist women students and a few quiet-ish boys. Ambitious young braves by contrast gravitated to Dr Tony Ward, and later perhaps to a Leavisite group around Dr Bob Jones.

Dr Harris, as I knew him, had a marvellously flexible and capacious mind. He was a scholar and above all a teacher, not much famed as a writer or orator. A very slight stammer sometimes occurred unexpectedly when he spoke.

He quoted to me once a letter by Keats contrasting the ‘egotistical sublime ‘ of a writer like Wordsworth, with ‘Negative Capability, [the capacity] of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts’. Being open, in fact. This was very much the quality of Bernard Harris’s own mind as I remember it. Only now do I also realise that the letter he cited was written just when Keats, as a very young poet, had made the painful little verse ‘In drear-nighted December’, which I had been obsessively copying out and learning by heart!

This episode was typical of Bernard Harris’s intuitive approach in tutorials. He sensed early on that I was concerned with the position of women, even though most of the syllabus featured so very few female writers in those days: Jane Austen and George Eliot, but no Elizabeth Barrett Browning, hardly even Virginia Woolf. He guided me to Victorian poets who had wrestled with ‘the question of woman’, marriage, class and evolution. Tennyson, Clough and others became the topic of my dissertation.

My old tutor was unusually sympathetic when I joined the women’s liberation movement in 1969, and when I later worked at Spare Rib magazine – many men of his generation were mocking or even actively hostile at the time. Later he nurtured Shaila Shah, who helped to found Outwrite international feminist magazine: followed by Sheba Publishers and then Lizzie Thynne, who went on to organise the first UK Lesbian and Gay Film festival and is now Professor of Film Studies at Sussex, focusing on women’s life histories.

As a tutor he was always flashing out so many brilliant ideas for things one could do and write, or think about. One day, for instance, hearing me voice a liking for certain East Coast writers, he suggested “ ‘Studies in a Dying Culture: Henry James, TS Eliot, Robert Lowell’, that would make a good book”. He gave permission for one to wander along many paths with helpful suggestions; a contrast to the strict track of FR Leavis or the impressively macho posture of some of our English department lecturers.

Bernard Harris was also interested in other arts. Theatre particularly, since he had come to York via the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford. I never see A Midsummer Night’s Dream without remembering that Titania (played in King’s Manor courtyard 1967 by Joanna Sanderson, now Joanna Gardner and a Jungian psychotherapist) was originally pronounced as Tie-tay-nia, in other words coming from the giant race of Titans who made the world before the human race began. That enriching piece of knowledge derives yet again from Bernard Harris.

He collaborated with Patrick Nuttgens, the charismatic head of York’s Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies, to create a special joint topic studying John Vanbrugh: Restoration dramatist, architect of Northern great houses, political activist and democrat, soldier and sometime French prisoner. The only published book to Bernard Harris’s name is an introduction to Vanbrugh’s bitter comedy The Relapse, arguing that the playwright ‘presents courtship and marriage not only with cynicism, but also with moral bravery and social impudence; qualities not much in evidence in his sentimental rivals’. (New Mermaid Classics 1971).

Our two tutors took a generously large number of us and our friends on a special trip to Vanbrugh’s Castle Howard and Seaton Delaval, both still in a state of postwar dilapidation and not really open to the public. Perhaps some of this liaising was enabled because both men, like Lord George Howard, were Catholics. The Harrises were from a Catholic enclave in Worcestershire and I have sometimes wondered if this gave my tutor a certain sympathy with outsiders. He also spoke once about his own time at Birmingham University just at the end of WW2, needing to make his voice heard against the war-veteran students who seemed so much more mature and confident.

“At York in the founding years we were incredibly privileged. We had the concentrated attention of our brilliant teachers, who also felt any of our achievements as their own. Together we were building something new and important.”

I still have on my shelves a Victorian copy of Tennyson’s long poem Maud, which my tutor gave me when my dissertation got high marks. As the university expanded so widely and fast, some of that close contact was inevitably lost despite the safeguard of the college structure. In fact on my first return visit to York in 1968 I found a student strike in progress against the cost of canteen food . Bernard Harris believed strongly in the college system so he resolved always to eat in his own college; sometimes this meant going through a picket line and sometimes it meant objectively supporting the strike. A typically interesting decision.

When I visited York some years later my former tutor was a Professor Harris much burdened with admin work: ‘I have too many hats on’. When I suggested that one or two of the hats could be dropped, he replied with grim fatigue: ‘Impossible – they are all cemented together and I can’t get them off my head’. Later still he became Provost of Goodricke and must have valued the renewed contact with students. It is fitting that his successor was Bill Shiels, who has devoted his whole adult life to York; he and I were part of the new intake of students gathering in King’s Manor courtyard in 1964.

Bernard Harris was also interested in visual art. He befriended York’s first artist-in-residence Honorine Catto, who came from a refugee background. The same applied to the respected painter Ruth Rix, then the young wife of a mature student. A large canvas by Ruth dominated the sitting room of the Harris’s home and must have been one of her first sales. He spoke of its refugee resonances with great sympathy and understanding, at a time when this was less than usual.

He was also very encouraging about my own drawings in my Vanbrugh dissertation, and must have written the reference for my postgraduate move to art history at the University of East Anglia -- a brief experience, but it led to a much longer time when I became an art reviewer.

“I was lucky enough to start writing about art at just the moment when the Black British Art movement was dawning. So I was able to appreciate and know some of those artists at the start of their careers, and even make a small collection of their work which I’m hoping to donate to the university.”

Music was another facet of my tutor’s multifarious mind. When Minster choral scholar Richard Evans set off for Munich to continue his singing career, he was saved from jobless near-disaster by moving to Hamburg where Bernard Harris’s good friend Dennis Clarke of the British Council found Richard teaching work and then a scholarship. Through those three years in Hamburg the Clarke family became Richard’s lifelong friends.

Another international contact came through BH’s work as an external examiner at Trinity College Dublin, where he got on well with RBD French: lecturer in Anglo-Irish literature, friend of Samuel Beckett, and author of satirical comedies and student productions. Harris and French both loved the theatre, both were more teachers and scholars than published writers, both remembered by generations of students.

Over the past year my connection with York has been renewed through the marvellous young students of the Gaza Solidarity Camp. To my surprise and delight, very many of them are taking English degrees. Their courses and topics are adventurous and wide-ranging beyond anything we could have dreamed of, but I like to think that Bernard Harris would have enjoyed their company and found a humane path to explore ideas with them.

Bernard Harris, Nouse 1983

Bernard Harris, Nouse 1983

Amanda's Art Collection held by Paul Sheilds, University of York Photographer

Amanda's Art Collection held by Paul Sheilds, University of York Photographer

Amanda's Art Collection

Amanda's Art Collection

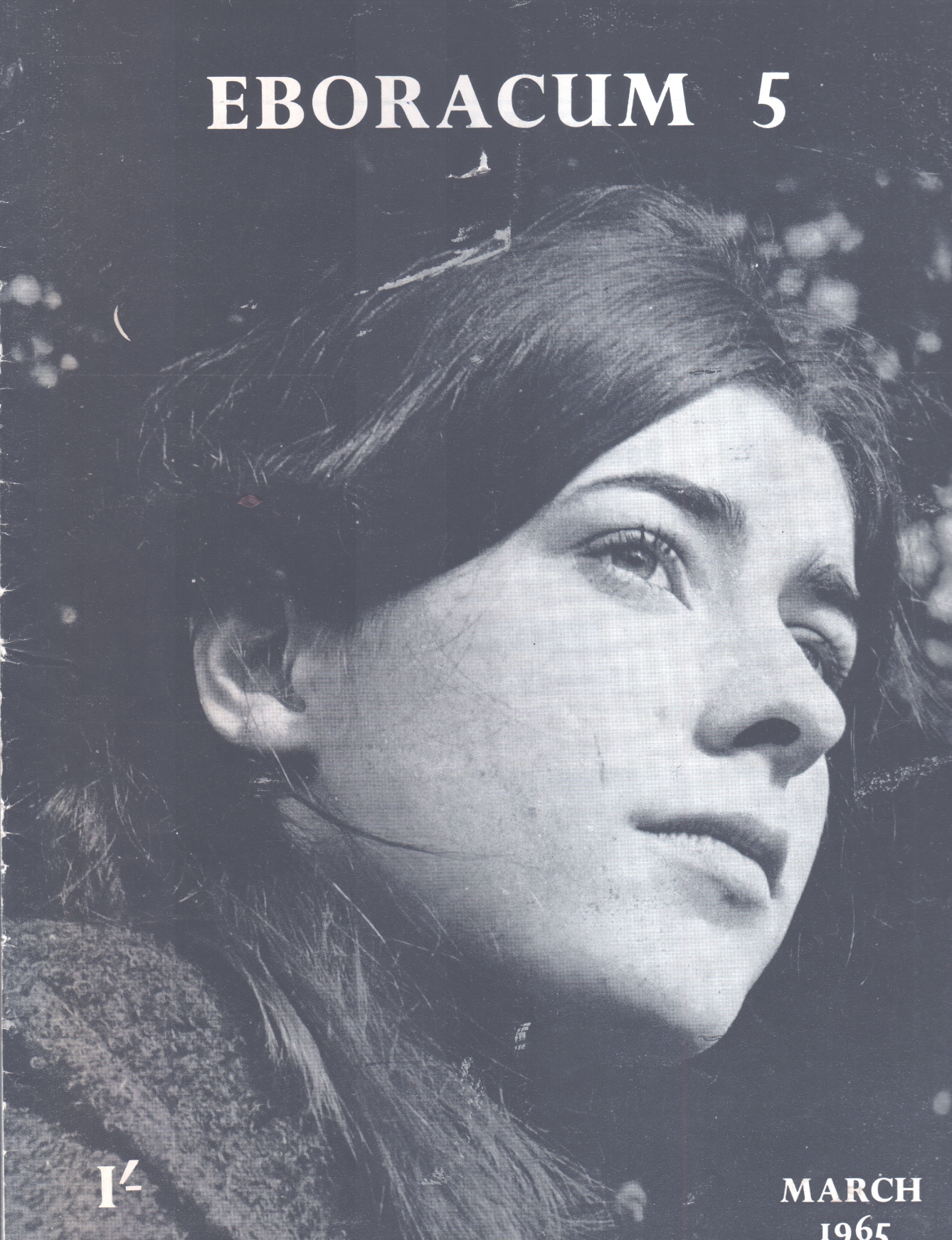

Amanda Sebestyen, on the cover of student magazine 'Eboracum'

Amanda Sebestyen, on the cover of student magazine 'Eboracum'

Professor Harris enriched the lives of so many students and and you too can help make sure future generations benefit from excellent teaching, world-class research and an environment that fosters new ideas. Please consider leaving a gift to the University of York in your will. Your legacy can help us continue attracting brilliant minds, support new discoveries and help us to open up opportunity to those who face more barriers.

Nigel Fountain

Politics, 1966

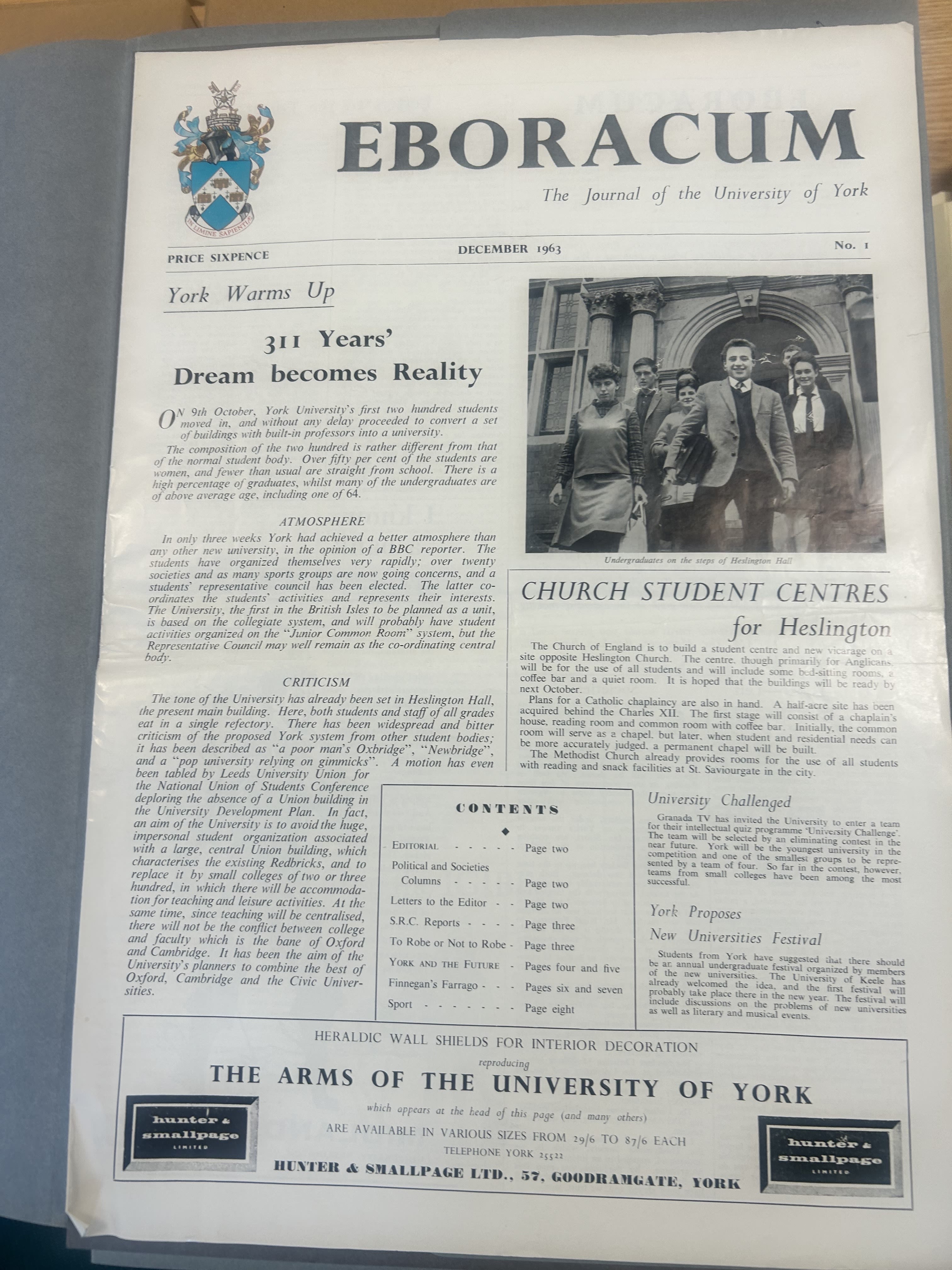

Eboracum 1, December 1963

Eboracum 1, December 1963

Eboracum 3, June 1964

Eboracum 3, June 1964

My first experience of the University of York came in March 1963 when I, a clueless teenager, arrived on a misty Sunday evening in the city for my interview the following morning with one Professor Alan Peacock, of whom I knew nothing. Two decades later he – seen, wrongly, as an ally of the right - would chair the Peacock committee into BBC financing, and displease Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher by not supporting its privatisation.

That day in 1963 my having explained that I was then a member of the Young Liberals, the Scot, who blended amiability with a slightly scary gravitas interrogated me on economic policy. After I had completed the simple task of making a fool of myself, Peacock, with a wintry smile, revealed that he had written Liberal Party economic policy.

That October I became part of the 214-odd initial intake - one unfortunate youth having been knocked from his moped and killed en route to Heslington. There was, I believe then uniquely at York, a balance of sexes among the undergraduates, plus a sprinkling of older, black African, Asian and disabled students, and even one old age pensioner.

“What there wasn’t was any appreciation in those grant–heavy days of just how lucky we, effectively a sixth form college attached to its very own university, were.“

And no-one noticed, or seemed to care that, apart from being a deeply impressive faculty, half our teachers seemed to be war heroes. Peacock had won a DSC for intelligence work in the Arctic, the English department’s Philip Brockbank served in Bomber Command, Education’s Harry Rée was in the Special Operations Executive, working with the French Resistance.

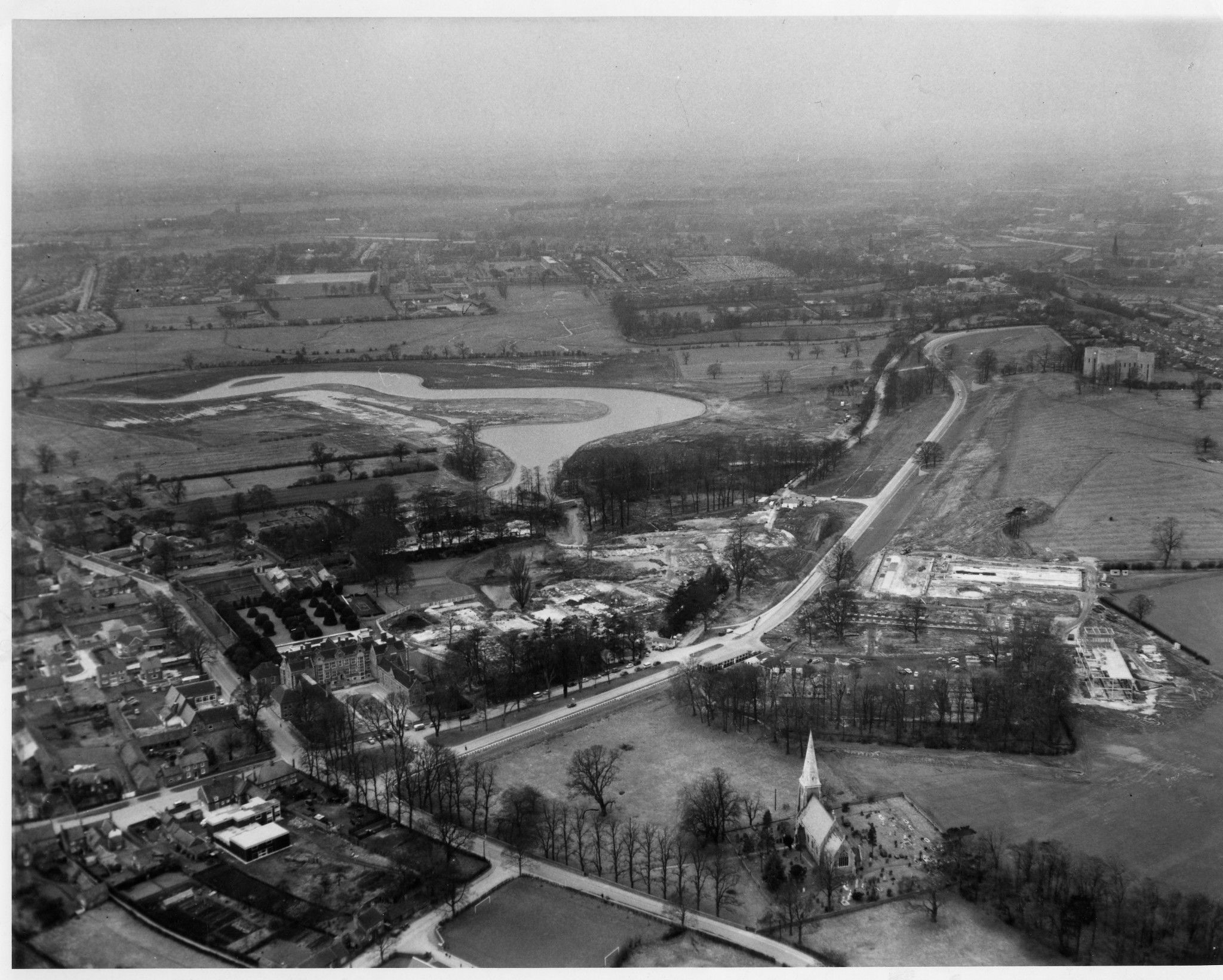

We meanwhile, got on with it. The University was Heslington Hall, and a small new lecture theatre in the village, next to a huddle of renovated ancient cottages. Next to the Hall was what appeared to be a swamp from which some new buildings were struggling into existence. We, or at least I, had little idea of the advanced architectural theory and practice around us, or indeed the significance of Europe’s (or was it the world’s) largest plastic lake snaking around the campus-to-be. But fellow student David Phillips and I, locating, from God knows where a rudimentary raft, set out Huck Finn-like to explore those waters. It was not the Mississippi, but it was a promised land of sorts.

It was a land where we did things that students in the early 1960s were supposed to do. Richard Rhodes, later a distinguished cineaste who died tragically young in a railway fire, set up a film society which, as I recall gathered at the long-gone cinema far out in the wild west of Clifton on Sunday afternoons. It was there that I saw Anna Karina in Jean Luc Godard’s Le Petit Soldat shortly after its release.

“Cinema is truth 24 times a second”

the trailer proclaimed. Wow, I thought. In a single afternoon I had taken in glamorous French movies, the Nouvelle Vague, and Anna Karina. It may have been a cold Sunday afternoon in York, and Godard might have been barely comprehensible (and lying, as I realised many years later) but this was living! I am still waiting for that little soldier’s return.

It was a land where we could become rock stars. A small group of us set off to Museum Gardens, where English undergraduate Philippa Stratton photographed us for our first album cover. Philippa took fine pictures, but the band did not measure up to the hype. A Yorkshire Evening Press journalist, Stewart Russell, came along for the story. Stewart was then a charismatic figure to me, (a journalist!) and generously pointed out to me that to be Charlie Watts, or even Ringo Starr it was first necessary to hold the drumsticks at the right end.

It was a land where I first tried out those dreams of journalism. The first student publication at York was born in an upstairs room in the first of those renovated cottages. Among its founders were Andrew Capes, Richard Malins and slightly later, myself. There was also David Burn, a fine cartoonist. The magazine’s name was Eboracum, York in Latin, God knows why.

Eboracum’s format was A4 (almost) and its glossy paper indicated financial support from our elders and betters. The three of us enjoyed a harmonious relationship even if I lacked Andrew’s taste for Flanders & Swann and railway recordings of Pacific class locomotives ascending the rising gradient into Hitchin station. We were not, in short, a team likely to produce cutting edge journalism, particularly with just an issue a term.

Also our two hundred strong audience didn’t particularly take to being mildly insulted by three not-very-smart alecks in a cottage down the road. So by issue two we were vaguely trying to master a don’t-insult-your-market style. It did not necessarily electrify our tiny captive readership.

By issue four in the Winter of 1964 it was year two, the two hundred had become five hundred, and a real university was edging into existence. One sunny autumnal day I had been sitting in the Eboracum office when I was visited by Michael Gray, later a respected scholar of Bob Dylan’s work, then looking for employment.

Within about five minutes he was the editor and I was out of the door. I noted his accession in Eboracum 4, and also the birth of a duplicated paper that November, edited by Richard Mann who with Brian Merton was, I believe, co-founder of Nouse. “Its emergence means, however that Eboracum must relinquish one of its two original roles,” I wrote grandly, “that of a general survey of life within the university - and must in future increasingly concern itself with the existence of a world outside.”

What Michael’s takeover did mean was the recognition of the existence of another sex within the university, which the original editorial team seemed not to have noticed. Thus it was that three women made it on to the masthead, and into print. This was in an era when, in the real world of Fleet Street the likes of Anne Scott-James, Marjorie Proops and Katherine Whitehorn were stars, and the first stirrings of what would become the women’s movement in the late 1960s were making themselves felt, even if I was blithely unaware of them.

Leaving Eboracum didn’t end an involvement with student journalism. I wrote for Nouse, and edited it for a term in 1965. Leading the front page, as I dimly recall, with an extremely boring story about the Queen and the CLASP (Consortium of Local Authorities Special Programme) architecture which dominated the discourse and the view from Heslington Hall briefly in those days. Her Majesty remained as inscrutable as ever on the subject and as for CLASP – well, nobody seemed to know about asbestos then.

Then 1966 came round. Unlike many of my peers I attended graduation, and shook hands with the Chancellor, Lord Harewood, who, thanks to a messy divorce, lasted about five minutes in the job. Then came life and journalism. Good, bad, and unexpected. But that is another story.

David Burn Drawing in Eboracum

David Burn Drawing in Eboracum

David Burns Caricature for Eboracum June 1964

David Burns Caricature for Eboracum June 1964

Nouse archives

Nouse archives

Nouse Issue 10, 28 October 1965

Nouse Issue 10, 28 October 1965

York was founded in 1963 on the principles of excellence and opportunity for all. We exist for Public Good.

“It's about how we work to open up opportunity, so that access to quality education is not restricted by anyone's postcode, family income, background or status as a refugee.” - Charlie Jeffery, Vice Chancellor and President of the University of York.

If you are considering leaving a gift in your will to help open up opportunity for generations of students, please contact our Legacy Manager, Maresa Bailey.

The Heslington Circle

We recently held our annual Heslington Circle event, to celebrate the impact of gifts in wills to the University. The Heslington Circle was established in 2012 to celebrate the community of friends, staff and alumni who have pledged, or are intending to pledge, a gift in their will to the University of York. Today there are over 280 members all over the world.

The event was hosted by Professor Charlie Jeffery, Vice-Chancellor and President of the University of York. We had the pleasure of listening to two of our student scholars, who told us about their journey to York and their experience and incredible successes while here. Accompanying our event we had music from our talented MA Music scholars and archivists from the Borthwick Institute for Archives on hand to share some interesting artefacts. Presenting on York Biomedical Research Institute and the Centre for Blood Research was world leading expert, Professor Gavin Wright. After a delicious lunch we ended the day with a wonderful tour of our historical Walled Garden from Jason Daff our Horticulture Manager.

Reflections and Thanks from our Scholars

Lurvïsh, BSc, Computer Science with AI, Ashinaga Scholar

I recently had the absolute honour of speaking at the Heslington Circle event. Standing in front of a room filled with people who’ve dedicated so much of their lives and legacies to my university, I felt a deep sense of responsibility and gratitude. It wasn’t just about telling my story; it was about showing the ripple effect of generosity, opportunity, and belief.

After losing my dad to Covid-19 in 2021, I wasn’t sure what the future would hold. My father was a teacher - someone who not only inspired me to pursue education but also embodied the belief that knowledge can change lives. When he passed, my mum became the sole provider for our family, and I knew I had to carry his legacy forward.

Shortly after his passing, I was fortunate to be selected as an Ashinaga Africa Initiative Scholar. The programme prepared me not only for university, but for a life of purpose. It reminded me that hardship can give rise to strength, and that education is a tool for collective uplift.

I’m now studying Computer Science at the University of York, where I’ve taken every chance to make a difference. I serve as the Department Rep for Computer Science, lead my college’s team as Halifax Badminton Captain, and support future students and events as a Student Ambassador. I also work as a Data Analyst for the Students’ Union, helping improve student experiences through data-driven insights.

“I carry with me a deep sense of gratitude - to the University of York, to my family and friends, to the donors who provided the scholarship, and to everyone who has supported my journey. Every lecture I attend, every opportunity I embrace, is made possible by the generosity and belief of others.”

The event was a reminder that we students are walking paths made possible by those who came before us. We, too, are part of the story being written.

Student Scholars and Ambassadors, Lurvïsh and Allyson

Student Scholars and Ambassadors, Lurvïsh and Allyson

Lurvïsh Presenting at the Heslington Circle Event

Lurvïsh Presenting at the Heslington Circle Event

Dawn, Music Scholar

Dawn, Music Scholar

Dawn Walters, MA, Music Composition, Terry Holmes Scholar

If you’d told me six years ago that I would now be studying for a Master’s degree in Composition at York, I wouldn’t have believed you. I was working a minimum wage job in a Post Office, and although people had suggested I should go back to Uni I didn’t think I could. However I was made redundant, and this started my journey back into study, and it has been the best time of my life. I really love York; both the city and the University. It was always my dream to study here, and although I have always sung and composed, having the opportunity to hone my skills at York has been an amazing experience for me.

Being awarded the Terry Holmes scholarship is a great honour, and has helped me achieve my aim of completing my Master’s degree doing something I love while also improving my abilities in and developing confidence to progress further as a composer and singer, and in study.

Coming into study later in life, combined with travel to and from Uni and looking after my children has meant that every penny counts, and I feel immense gratitude for receiving the scholarship. My heartfelt thanks to Terry Holmes and all the OPPA donors.

If you would like to hear some of my compositions, the link to my SoundCloud is below.

Thank you to our Heslington Circle members for supporting our current and future students.

If you would like more information about the Heslington Circle, please contact me directly at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk

Our next YuPlan webinar: Free solicitor advice on will writing

Your next opportunity to get free advice on estate planning, writing a will and inheritance tax.

Thank you!

Your legacy gift is our future.

I hope you have enjoyed reading those fascinating early memories of the University and about the very real difference scholarships have on the lives of students like Lurvïsh and Dawn.

Many of our legacy donors have a special relationship with the University. Maybe like Amanda, Diana and Nigel you met special friends here, perhaps your degree was the catalyst for a successful career or by joining a club, society, activity - like Nouse, you found something else that made a huge impact on your life.

Pledging a legacy gift will cost you nothing today, but will be of tremendous value to the University in the years to come. Once you let us know your wishes, we'll invite you to become a member of the Heslington Circle, which was founded to thank those generous, alumni, staff and friends who have chosen to remember the University in their will.

To learn more about how a gift in your will can make a real difference, please contact me directly at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.

For further information on leaving your legacy to York, you can download our legacy brochure.

To discuss anything in this newsletter further, please contact the Legacy Manager, Maresa Bailey, at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.