“Life's most persistent and urgent question is, 'What are you doing for others?'”

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The Legacy Newsletter | Edition 18, December 2025, The University of York

This December, as the holiday season calls us to reflection, we turn to Dr. King's urgent question as our guide. A true legacy isn't simply what we leave behind, but the opportunities we secure for others.

This month, we feature the inspiring stories of University of York alumni and Heslington Circle members, John Eifion Jones and Andrée Rushton, whose time at York led them to invest in the University's future through a gift in their will. Both John and Andrée mention how fortunate they were to receive a local authority grant for living expenses and free tuition fees.

“I am bequeathing £60,000 to the University of York. It’s just delayed repayment really. I think it behoves all of us who had such luck to make a contribution.” - John Eifion Jones

For today’s students, finances are the biggest stressor in life, and with the cost-of-living crisis in the UK, many young adults are being priced out of higher education. Once in higher education, most students have to work alongside their studies. The findings of the Student Academic Experience Survey (SAES) 2025, published by the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) and Advance HE, revealed a dramatic rise in the proportion of full-time undergraduates undertaking paid work working during term time - now at 68%, up sharply from 56% in 2024 and 42% in 2020. For many of our students, work is not about experience, but financial survival.

In this edition we also meet Malak Farag, the first recipient of the Sam Pegram Scholarship, whose life-changing journey demonstrates the immediate, global impact of focused philanthropy. Malak's story, and the mission of the Sam Pegram Scholarship, perfectly reflect the spirit of compassion championed by the York Sanctuary Fund.

We invite you to take festive action this year: whether by securing a lasting legacy for the University's future, or by supporting initiatives like The York Sanctuary Fund to offer sanctuary and opportunity to those who need it most.

To discuss leaving legacy to York, please email me at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk or call me on 07385 976145.

Maresa Bailey, Legacy Manager

John Eifion Jones

Heslington Circle Member | BA History, 1972

"Stepping off the train under the magnificent curved Victorian canopy of York station in the autumn of 1969 was a grand entrance to adult life. Just outside lay the ancient city walls, and the Gothic towers of York Minster beyond. What a place to read History! I had suddenly left behind childhood in rural North Wales for college. I was a well-grounded, reasonably confident fellow but perhaps sheltered from the world. I had never tasted beer until I arrived in Heslington.

I chose York because it was a campus, collegiate university. This assured decent accommodation, no damp lodgings or shared digs or crusty landladies. And the colleges conferred scale and a sense of identity. I settled into Alcuin quickly. On my corridor were two chemists, a mathematician, an English and Philosophy student, a musician, and a bouncy social scientist who later became a Tory MP. Essentially this was sheltered accommodation for young adults, a managed transition to independence. And it came at no cost to my generation. Tuition fees and maintenance grants were paid.

"That is why I am bequeathing £60,000 to the University of York. It’s just delayed repayment really. I think it behoves all of us who had such luck to make a contribution. I have also donated £1,000 this year to the York Sanctuary Fund - on which more later."

Another factor for choosing York was the strong reputation of the History Department under Gerald Aylmer; with his measured tread and considered manner, he was the epitome of an academic scholar. Gordon Leff and Richard Fletcher were outstanding medievalists. The crowded brain and caring manner of my personal tutor Dwyryd Jones left their mark. Likewise Jim Walvin, a pioneer of anti-slavery history, whose approachable style set us at ease in seminars.

But 1969. Student protests. The occupation of Heslington Hall. Revolution was in the air. Well, sort of… we historians were a clannish lot, with long reading lists. Weekly deadlines. Longhand notes. No computers, essays in pen and ink. My own act of rebellion was to join the University’s Conservative association.

Study dominated, but college shaped our lives. Alcuin was run with quiet efficiency and fairness by the college secretary, who I believe was called Pauline Warby. She ensured peace and concord in the residential blocks, oversaw the fine dining hall, the porters, everything. I am pleased to highlight here the unsung contribution of the college secretaries to the running of the University of York.

The city of York was an inspiring backdrop. Choral evensong beneath the soaring stone and stained glass of York Minster lent perspective to life; one could unpeel the centuries walking those narrow historic streets, and the chattering locals in the marketplace off Stonegate seemed just as timeless.

Memorably, a new world opened for me when I heard George Malcolm play Bach on the harpsichord in the Lyons Concert Hall. I have met many remarkable people in York and Fleet St, but only with Bach do I feel truly in the presence of genius.

Given my lifelong ambition to become a journalist, my contributions at York were slight. Some film reviews and contributions to YSTV was about it. But my resolve was clear since early childhood when I was captivated by the photojournalism of Picture Post magazine, notably its coverage of the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian revolution in 1956.

After York I moved to London thanks to a great Alcuin friend, Ian Kirkland, who gave me house room whilst pitching for a job in journalism. My break came when instead of long inflated applications I decided on the honest approach. A one paragraph letter:

“I have wanted to be a journalist since I was about five. I can type, I have a good degree in history and I’m prepared to do whatever it takes to get started. Please let me know if you have anything going.”

It struck a chord with the chief at United Press International (UPI), a news agency rivalling Reuters. Brevity appealed to Greg Jensen, who became my mentor and lifelong friend. It was a steep learning curve as veteran correspondents taught me how to write fast, accurate, breaking news. I had gone from studying history to recording the first draft of history. Ulster, IRA bombings, Charles and Diana, the Thatcher era. Fortnightly foreign press briefings in the front parlour at Downing Street were a highlight.

Telegraph London was also UPI’s headquarters for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. So weeks alternated between filing London copy and desking and editing world news. Apartheid South Africa, Kissinger’s diplomacy, divided Berlin, Brezhnev’s Moscow, the Iranian Revolution. The pace was relentless, 24 hours a day. It was thrilling beyond my childhood dreams. UPI was brilliant with words, not so clever with figures and the company was going bust - effectively bankrupted by the cost of reporting Vietnam.

But I struck lucky once more. The Daily Telegraph was setting up a worldwide syndication service to rival The New York Times. I was approached to set it up in 1987 as the age of computers dawned.

Foreign news, comment, features, sport, business, I had the run of the Telegraph to produce a daily news feed augmenting agency material with the perspective and exclusives of a heavyweight newspaper. Intrepid coverage of the Iran-Iraq war helped get us established, with distribution across the Commonwealth a mainstay. The Telegraph’s strong sports coverage was another plus. Within a few years Daily Telegraph copy was being published across the world. Dublin, Madrid, Dubai, Johannesburg, Calcutta, Tokyo, Melbourne, Auckland. It’s been a wonderful life, a front row seat as an observer of history. Excitement yes, but also deep concern at so much persecution and repression. That’s why I became a supporter of The York Sanctuary Fund. It provides support for students, academics and human rights defenders affected by conflict or persecution, allowing them respite and study at York. The fund currently supports 34 scholars from 20 countries - more than 100 from 52 nations since 2008.

All my life I believed the world would become a better place. Mandela’s freedom, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the transformation of eastern Europe, gave me cause for hope. Alas, democracy has never been in worse shape. We need to support those fighting to make it a fairer place.

Please consider giving to the York Sanctuary Fund."

- John Eifion Jones

Lower Petergate, 1960s

Lower Petergate, 1960s

Alcuin College, 1960s

Alcuin College, 1960s

Excerpt from student newspaper Nouse, March 1970. 'Hes. Hall Occupation Ends.'

Excerpt from student newspaper Nouse, March 1970. 'Hes. Hall Occupation Ends.'

Ticket for University of York Music Week, 1 to 9 March 1969, 'To mark the opening of the Lyons Concert Hall'

Ticket for University of York Music Week, 1 to 9 March 1969, 'To mark the opening of the Lyons Concert Hall'

Continuing a Legacy of Compassion: Malak Farag, the First Sam Pegram scholarship holder

The University of York’s campus is home to inspiring stories of compassion, resilience, and hope. Among them shines the extraordinary legacy of alum Sam Pegram, a humanitarian whose life and tragic passing created a ripple of positive change through the Sam Pegram Scholarship. This scholarship, established in Sam’s memory, now supports international students dedicated to advancing human rights. Malak Farag, the first ever student to receive this scholarship, embodies the spirit of sanctuary and justice at the heart of York Law School, ensuring Sam’s mission continues.

The Sam Pegram Scholarship provides one international student with full funding for the LLM in International Human Rights Law and Practice at York Law School and the Centre for Applied Human Rights. The award covers tuition, accommodation, travel, and living costs thanks to the generosity of the Sam Pegram Humanitarian Foundation. Its aim is simple, but profound: to enable talented individuals to pursue careers supporting people ‘on the move’ - refugees, migrants, and communities facing exclusion and adversity.

The scholarship honours the life of Sam Pegram, who dedicated his career to humanitarian causes. After volunteering in Jordan, Sam came to York and flourished in the LLM programme, known for his thoughtful approach and deep empathy. He later joined the Norwegian Refugee Council in Geneva, using his training to create tangible difference. In 2019, Sam’s life was cut short in the Ethiopian Airlines crash en route to Nairobi for humanitarian work. His spirit, remembered for kindness and advocacy, lives on through every scholar supported in his name.

For Malak Farag, receiving the very first Sam Pegram Scholarship was both an honour and a life-changing opportunity. Growing up in Egypt, surrounded by refugees and shaped by migration issues, Malak’s passion for supporting displaced communities began at home. Her academic pathway mirrored Sam’s: a bachelor’s in International Relations followed by the LLM at York, inspired by the same commitment to serving refugees and those on the move.

Malak’s career has spanned volunteer work with refugee NGOs across continents and roles with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). At York, she has embraced every opportunity: editing for the York Law Review, placements with global human rights organisations, and research assistantships - each stepping stone guided by an unwavering focus on justice and social impact.

Malak reflects, “I truly wouldn’t be here without it. This scholarship didn’t just give me the chance to pursue a degree – it changed the course of my life. This year has been one of incredible growth and learning, and I carry deep gratitude every single day for the opportunity I’ve been given.”

Receiving the scholarship connected Malak not only to resources and academic growth, but also to Sam’s values: “Being chosen as the first scholar is both a profound honour and a great responsibility, and I am forever grateful to Sam’s parents, Mark and Debbie, for entrusting me with the chance to be part of Sam’s legacy. This is not something I take lightly, it is a privilege that shapes how I approach my studies, my work, and the way I want to contribute to the world. Sam’s empathy, compassion, and commitment to making a difference in the lives of others continue to inspire me every day. Carrying his values forward has become a guiding light for me, one that pushes me to not only pursue excellence but also to live with kindness, courage, and purpose. To be connected to Sam’s memory in this way is the greatest privilege of my life, and I will always strive to honour and uphold the values he embodied.’’

Malak’s story is one of solidarity and transformation. She recognizes the broader impact: “This contribution does more than just fund education - it completely changes someone’s life, and multiplies the impact for the communities that scholar serves. Supporting students in this way also means supporting advocates who do crucial work in their own communities”.

The Sam Pegram Scholarship is more than just financial support. It is an act of solidarity between those who give and those who strive to make the world more just. Scholarships like Sam’s train humanitarian workers and social justice advocates, amplifying York’s role as a sanctuary for the excluded and a seedbed for global change.

For anyone considering supporting the York Sanctuary Fund or creating a legacy gift, Malak’s words resonate: “There are countless people with extraordinary potential who may never get the chance to fulfill it simply because they lack safety or the financial means to pursue education. Supporting scholarships like this doesn’t just change individual lives, it transforms entire communities and sends a powerful message that we stand with the world’s most vulnerable. It is an act of faith and investment in human potential, that given the chance, people will rise and reshape the world.’’

Sam Pegram’s legacy is rooted in empathy, action, and hope. Scholars like Malak keep alive his dedication to seeing ‘the best in everyone’, working tirelessly to advance justice for refugees and migrants. Through gifts in-memory, donors help shape a future where York students can create meaningful impact, generation after generation.

“We are so proud to sponsor this scholarship in Sam's memory. It is an important part of our vision for Sam's Legacy to give opportunities to talented and committed early career humanitarians that they may not be able to achieve without financial support. Sam used a small inheritance from his Nana to help him volunteer with refugees in Jordan and he then progressed into paid work. It has been an absolute pleasure to meet Malak and see the way she has grasped this opportunity with both hands. We feel so positive about the difference she will be making to other people's lives in her career and we are proud to have found such a strong ambassador for the scholarship and Sam's Legacy.” - Debbie and Mark Pegram

If you would like to know more about leaving a gift in-memory, or supporting the Sanctuary Fund, please contact Maresa Bailey, Legacy and In-Memory Manager at the University of York.

Sam's parents Debbie and Mark, with Malak, the first Sam Pegram scholarship holder.

Sam's parents Debbie and Mark, with Malak, the first Sam Pegram scholarship holder.

Sam's parents, Debbie and Mark, with Sam.

Sam's parents, Debbie and Mark, with Sam.

Mark, Debbie and Malak enjoying an ice cream.

Mark, Debbie and Malak enjoying an ice cream.

Sam as a child.

Sam as a child.

Sam working in Jordan in 2015.

Sam working in Jordan in 2015.

Andrée Rushton

Heslington Circle Member | BA History 1967

Andree Rushton

Andree Rushton

Heslington Hall, 1963

Heslington Hall, 1963

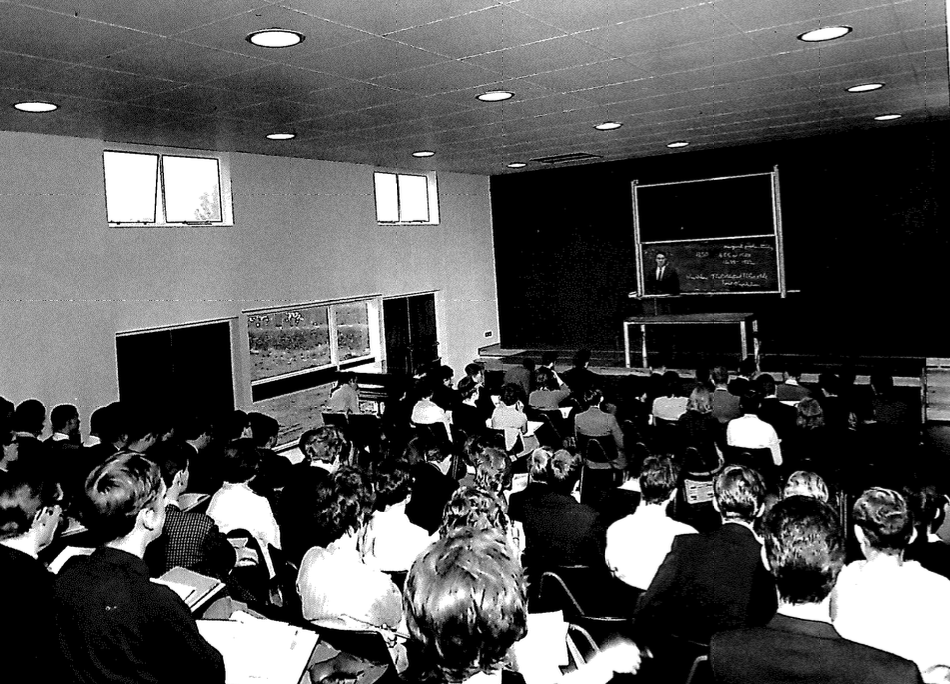

Lecture theatre, 1960s

Lecture theatre, 1960s

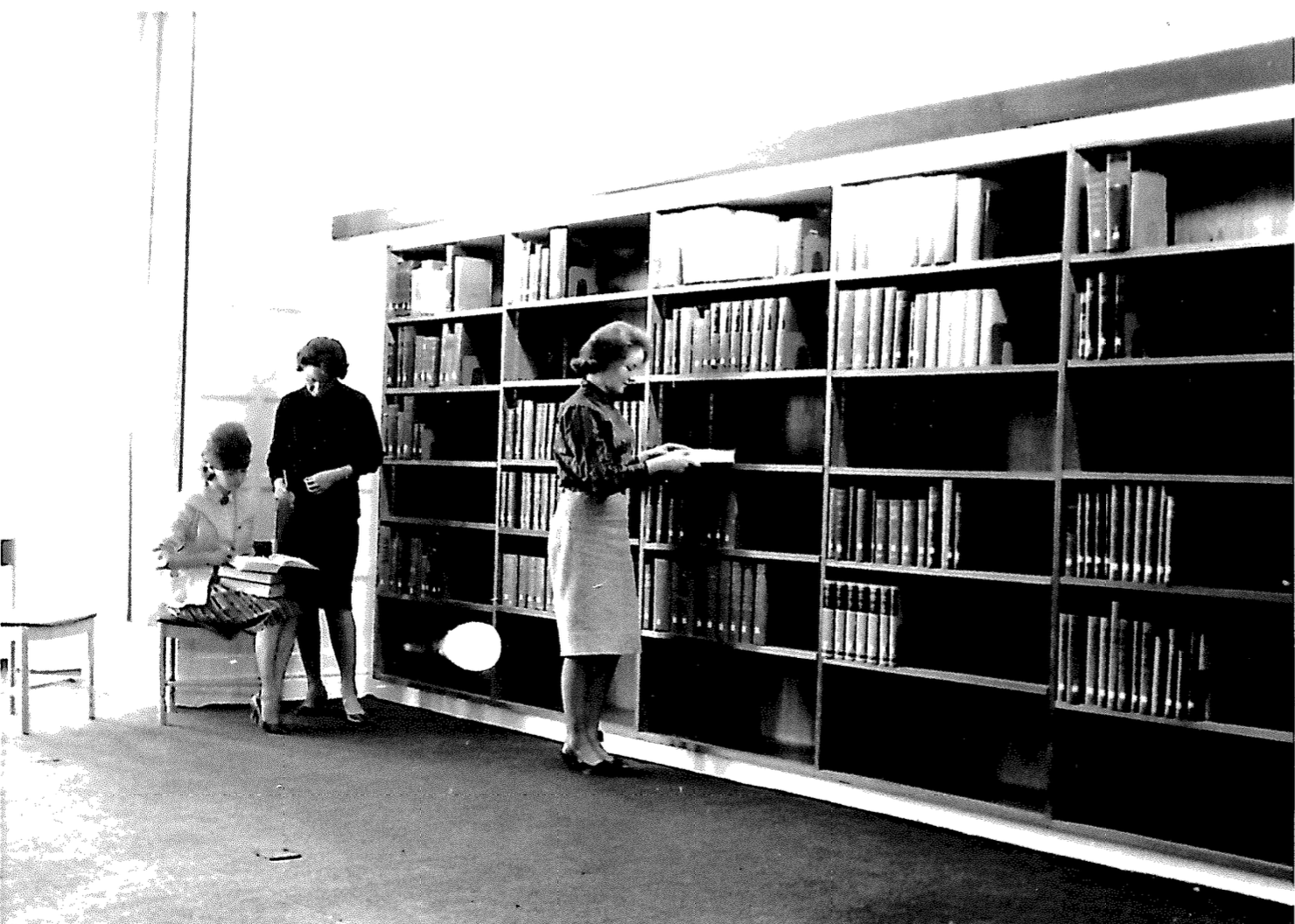

Library, 1960s

Library, 1960s

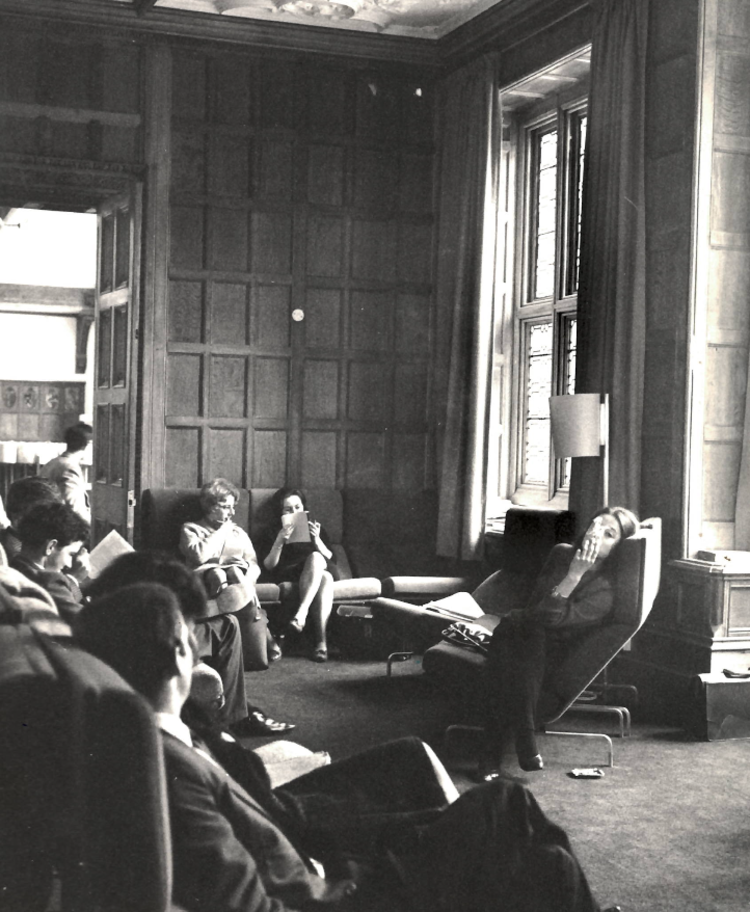

Micklegate House, 1960s

Micklegate House, 1960s

I studied history at York from 1964 to 1967. I had gone to state schools - two primary schools and after passing the 11+ to a Sussex grammar school, with a spell of three years at an RAF school in Singapore in the middle of secondary education. I was the first person in my family to go to university and it felt like a big change in life.

I chose York because, with only a few hundred students, it was a small university and seemed less daunting than somewhere older or more established. My main memory of the interview is that, applying to study history, I confessed to reading historical novels and came away having mentioned Georgette Heyer, Dennis Wheatley and Jean Plaidy. I was convinced I had failed the interview and was surprised and delighted to receive a letter offering me a place!

There was no problem with funding. My local authority paid for the fees which were £75 a year. I applied for a student maintenance grant and was awarded £300 a year with my father expected to pay the remaining £40 a year. He said he would pay it in kind as I was living at home during vacations. My grant didn’t feel like enough to live on, so I spent most of the vacations working on a conveyer belt in a perfume factory near where I lived in Surrey, and at Christmas I delivered the post.

Arriving in York in October 1964, I was part of only the second intake. Many of the other students at York had been to public or private schools and seemed to be from a different world, but there were plenty of students like me from state schools.

I felt privileged to be at a new, small university with plenty of access to staff. We had lectures, seminars and individual tutorials and there was a palpable sense of being part of something new and exciting.

History was taught, appropriately, at Kings Manor in the centre of York. My memory is that we began in 1300 and that anything later than 1914 was current affairs and so avoided, although one York friend assures me that she studied the 1930s. Professor Gerald Aylmer was an able teacher of the English Civil War and Gwyn Williams gave such a rousing lecture about the French Revolution that one student got up a petition in the (vain) hope of persuading him to repeat it. Lectures near the main courtyard were punctuated by the cries of the peacocks who seemed to live there, provoking a ripple of amusement. All but one of the history lecturers were men and except for a few queens and other notables all the history we studied was about men. But I wasn’t yet a feminist. That came later, in consciousness raising groups in London.

I had worked hard at school but I wasn’t a conscientious student at York. I lacked discipline and spent far too much time getting to know the fascinating people I found myself amongst – the other students. I still benefited from those three years enormously. Some of the friendships I made there have lasted a lifetime and I value them greatly. I have retained my interest in history. In a city with a Minster and so many parish churches, I developed a lifelong interest in church architecture. In my middle years, because of holidays nearby, I became fascinated by William Beckford and his Wiltshire estate, contributing to the journal of the society in his name and collecting biographies of him. In retirement I have written three historical novels set in wartime England and France.

We were all in digs for our first year and so hardly needed to go to the main university campus at Heslington, although of course we all visited it and attended special lectures there or joined in various activities. Another student and I did voluntary work with a local psychiatric hospital at Naburn. That is, once a week during term-time we took patients to York tearooms and hoped they would behave reasonably well, which they did most of the time.

I owe a lot to the University of York and have always remembered those three years as a special time in life. One evening towards the end of my third year at York, I attended a meeting about the Six Day War which had just taken place in Israel. The Jewish Agency was asking for people to go to Israel. With no clear idea of what I wanted to do in life and ignoring the fact that they were looking for Jews, not gentiles, I was determined on going and thanks to the influential father of a York student friend, I was able to do so. I spent six months in Jerusalem, helping to clean up Mount Scopus and learned to speak some Hebrew. Despite this latest and most terrible war, I still hope for a two-state solution so that Palestinians and Israelis may exist in peace.

Back in England again, I became a social worker, later adopting two children with my husband, Alan. Once the children were settled in school, I worked as a research assistant for a Labour MP at the House of Commons and later I took the civil service exams and went into the Department for Education. I have been retired for 20 years now and I am secretary of the Friends of Putney Library. In retirement I have written a book about our experience of transracial adoption. I have also written three novels, all set during and after the second world war. The War Baby is about a young woman who reluctantly gives up her baby for adoption and what happens years later when her adult son seeks her out. The Hanged Man shows a group of Brits sharing a house in present day southern France and discovering the story of its wartime occupants. Nicole’s War, inspired by my mother’s escape from France during the war, introduces a young British woman living in Paris during the Nazi occupation.

I am leaving money to the University of York in my will (and to Manchester University in memory of my husband) because these days universities appear to receive little government support. I should like my contribution to support students experiencing financial hardship.

The Heslington Circle

The Heslington Circle is our way of recognising the generosity of those who pledge their support to the University in their will by inviting you to an annual reception and keeping you informed of developments within the University.

If you would like more information on joining the Heslington Circle, please contact me at Maresa Bailey, Maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.

Our next event will take place on 25th April, 2026 and will include insights on world class research being undertaken at the University. For example, Dr Jihong Zhu, a robotics expert from the University of York’s Institute for Safe Autonomy will be presenting on his work developing a mammobot to help people with mobility issues get better access to breast screening procedures.

To register your interest for the 2026 event please do so below:

If you are interested in coming to York the weekend of the event, we will be arranging an informal dinner at a local York restaurant on the evening of Friday 24th April. Please let me know if you would like to be added to the guest list at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.

There are also special alumni accommodation discounts at Franklin House on campus or Malmaison York. To take advantage of the offers, join our York for Life platform and connect with alumni around the world.

Our next YuPlan webinar on 22 January 2026

Our next YuPlan, your free will writing and estate planning session will take place online on Thursday, January 22 from 5pm to 6.30pm. This online event is a partnership between local York solicitors Crombie Wilkinson and the Office of Philanthropic Partnerships and Alumni. You'll be able to get free advice on:

- Will writing and inheritance tax advice

- Estate planning

- Power of Attorney

- Foreign dimensions

- Q&A - Ask the experts

There will also be a special opportunity to win a free single or joint will through Crombie Wilkinson by completing a simple post event survey.

We look forward to welcoming you in January. If you have any questions please contact: Maresa Bailey, Legacy Manager, at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.

Gifts In Wills and Tax Benefits

The University of York is an exempt charity under Schedule 3 of the Charities Act 2011. As such, any gift within your will falls outside of inheritance tax. Giving as part of your will planning can reduce the Inheritance Tax rate on the rest of your estate from 40% to 36%, if you leave at least 10% of your 'net estate' to a charity.

Thank you!

I hope you enjoyed reading this edition of the Legacy Newsletter. The photographs shown here are of a special heritage tree planting project in memory of Caitlin Cole, a biology student here at York, who sadly passed away in 2019. Caitlin’s family and friends generously funded this project along with an earlier project to establish Caitlin’s Wood on Campus East.

Jason, the University's Horticulture Manager, and his team at the tree planting session.

Jason, the University's Horticulture Manager, and his team at the tree planting session.

The recent planting took place in the Walled Garden behind Heslington Hall. Jason Daff, Horticulture Manager in the Department of Biology, led the days activities which involved the re-introduction of traditional heritage apple trees. You can read about the forgotten fruits of Heslington Hall’s Walled Garden here. We hope to transform the Walled Garden into a space to tell the story of plants and their role in feeding, healing and fuelling our world. It will be a demonstration of our commitment and responsibility to educate new audiences about the role that plants can play in creating a more sustainable world.

Maresa Bailey, Legacy Manager

Maresa Bailey, Legacy Manager

If you would like to have a conversation about finding a special way of remembering a loved one such as setting up an award like the Sam Pegram Scholarship or contributing to the Walled Garden project like Nick and Colette Cole, please get in touch. If you would like to discuss leaving a gift in your will, to support future generations of Yorkies, like John and Andrée, I would be happy to arrange a telephone call or perhaps a cup of tea on campus. Please contact me at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.

For further information on leaving a legacy to York, you can download our legacy brochure.

To discuss anything in this newsletter further, please contact the Legacy Manager, Maresa Bailey at maresa.bailey@york.ac.uk.