YORK RESEARCH JOURNEYS

Professor

Helen Cowie

YORK RESEARCH JOURNEYS

Professor

Helen Cowie

Helen’s interest in history started early. As a child, she enjoyed visiting museums, castles and other historical sites and was fascinated by a range of historical topics, from Inca mummies to the Jacobite Rebellion. She also enjoyed reading about the past and watching historical dramas.

“I think what drew me to it was the story element. I liked learning about the lives of historical characters. I wanted to know more about Tutankhamun, Evita and Bonnie Prince Charlie. I wanted to understand what life was like in a medieval castle or a Victorian workhouse.”

The questions and curiosity that arose led Helen to study History at university, where she was able to take modules on the French Revolution, twentieth-century Eastern Europe and the Spanish American Wars of Independence.

“I was always drawn to the slightly different bits of history, the ones you don't necessarily do at school. As an undergraduate, I remember writing essays on the Mexican Revolution, the Tupac Amaru Rebellion in Peru and the downfall of Ceaucescu in Romania.”

Today, as a professor of modern history, it is still the unusual parts of history that speak to her. While most historians tend to focus their attention on the lives of humans in the past, Helen has chosen to uncover the often forgotten lives of animals. This interest came about during her undergraduate studies. As she was soon to discover, however, the topic of animals in the past was not on a lot of people's radars.

“People just weren't looking for animals in historical sources. But once you start searching, the animals are there, in newspaper articles, diaries, letters, photographs, paintings and material culture. Though curated by humans, these written and physical remains give us an insight into how animals lived and died in the past.”

Helen Cowie is Professor of Modern History in the Department of History at the University of York. Her research focuses on the history of animals, and in particular how human–animal relationships have evolved and changed through time.

Helen’s interest in history started early. As a child, she enjoyed visiting museums, castles and other historical sites and was fascinated by a range of historical topics, from Inca mummies to the Jacobite Rebellion. She also enjoyed reading about the past and watching historical dramas.

“I think what drew me to it was the story element. I liked learning about the lives of historical characters. I wanted to know more about Tutankhamun, Evita and Bonnie Prince Charlie. I wanted to understand what life was like in a medieval castle or a Victorian workhouse.”

The questions and curiosity that arose led Helen to study History at university, where she was able to take modules on the French Revolution, twentieth-century Eastern Europe and the Spanish American Wars of Independence.

“I was always drawn to the slightly different bits of history, the ones you don't necessarily do at school. As an undergraduate, I remember writing essays on the Mexican Revolution, the Tupac Amaru Rebellion in Peru and the downfall of Ceaucescu in Romania.”

Today, as a professor of modern history, it is still the unusual parts of history that speak to her. While most historians tend to focus their attention on the lives of humans in the past, Helen has chosen to uncover the often forgotten lives of animals. This interest came about during her undergraduate studies. As she was soon to discover, however, the topic of animals in the past was not on a lot of people's radars.

“People just weren't looking for animals in historical sources. But once you start searching, the animals are there, in newspaper articles, diaries, letters, photographs, paintings and material culture. Though curated by humans, these written and physical remains give us an insight into how animals lived and died in the past.”

"I'm interested in finding out about the lives of animals in the past and recounting their experiences. How were they treated? How did they behave? How did they shape the world around them?"

"I'm interested in finding out about the lives of animals in the past and recounting their experiences. How were they treated? How did they behave? How did they shape the world around them?"

Uncovering the animal voice

While discovering what animals’ lives were like is difficult, this did not stop Helen. According to her, there are plenty of rich historical accounts that can tell us about the changing relationships between humans and animals or reveal how people felt towards individual animals. And although animals cannot speak our language, Helen believes we can, and should, still tell their stories.

“I'm interested in finding out about the lives of animals in the past and recounting their experiences. How were they treated? How did they behave? How did they shape the world around them?”

The real difficulty in her research, says Helen, lies in understanding the thoughts and feelings of the animals themselves and viewing them as historical actors. Given that the sources about animals were written by humans, this can be challenging, but there are ways of foregrounding the animal experience.

“Some historians are drawing on the writings of hunters, soldiers and zookeepers to learn about the animals they worked with. Others are drawing on modern studies of animal behaviour to interpret animal actions and emotions in the historical record. One historian, for instance, has attempted to reconstruct the journey of a young female giraffe from Sudan to Paris in 1827 from the perspective of the animal by applying modern knowledge about giraffe psychology and physiology to contemporary writings.”

Not all animals are recorded equally in historical records, however, and Helen emphasises that some animal lives are more recoverable than others.

“The quality of information we have about animals varies significantly. Pets, for example, tend to generate the most traces because of their close relationship with humans. Zoo animals also leave behind a clearer footprint because of their exoticism, visibility and proximity to humans. Domesticated livestock and laboratory animals, however, tend to receive less attention and are more often presented in the form of statistics. So it will probably be easier to write the biography of a famous zoo animal like Jumbo the elephant than to reconstruct the life story of a sheep in Patagonia or a rat in a laboratory.”

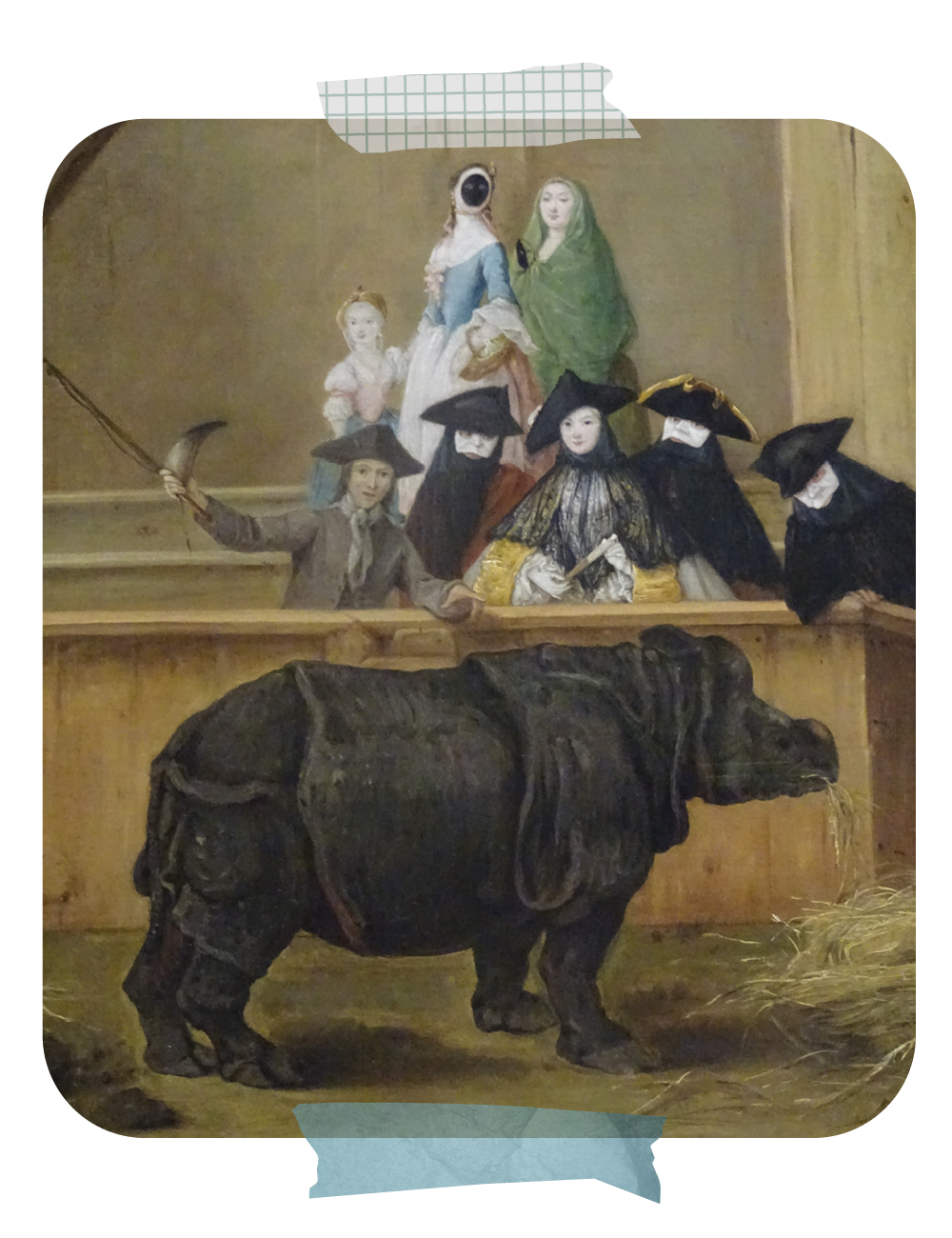

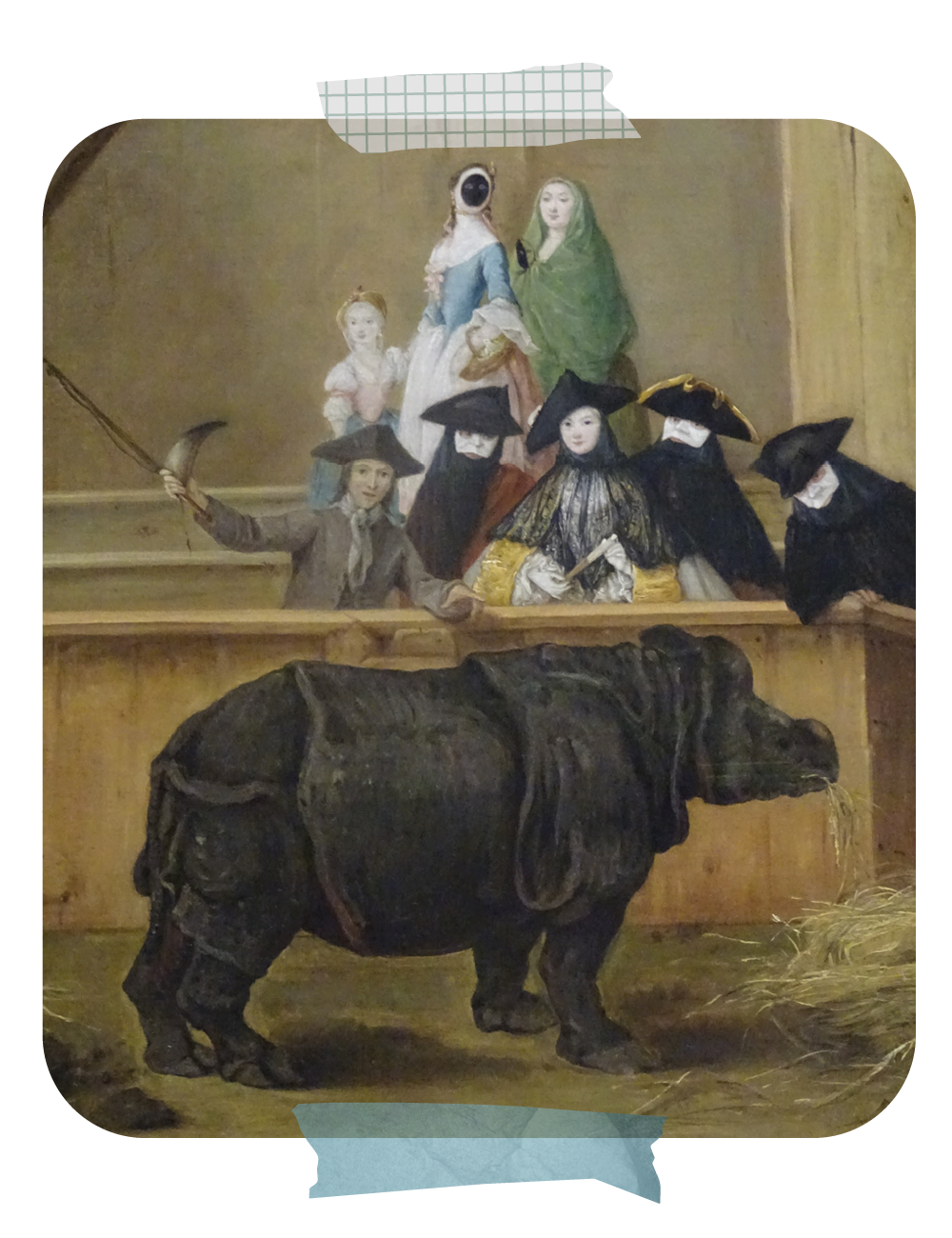

In 1751 Pietro Longhi painted this picture of Miss Clara, a rhinoceros exhibited at the Venice Carnival. A showman wields her lost horn and a whip in front of masked members of the audience. Image: the National Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

In 1751 Pietro Longhi painted this picture of Miss Clara, a rhinoceros exhibited at the Venice Carnival. A showman wields her lost horn and a whip in front of masked members of the audience. Image: the National Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Uncovering the animal voice

While discovering what animals’ lives were like is difficult, this did not stop Helen. According to her, there are plenty of rich historical accounts that can tell us about the changing relationships between humans and animals or reveal how people felt towards individual animals. And although animals cannot speak our language, Helen believes we can, and should, still tell their stories.

“I'm interested in finding out about the lives of animals in the past and recounting their experiences. How were they treated? How did they behave? How did they shape the world around them?”

The real difficulty in her research, says Helen, lies in understanding the thoughts and feelings of the animals themselves and viewing them as historical actors. Given that the sources about animals were written by humans, this can be challenging, but there are ways of foregrounding the animal experience.

“Some historians are drawing on the writings of hunters, soldiers and zookeepers to learn about the animals they worked with. Others are drawing on modern studies of animal behaviour to interpret animal actions and emotions in the historical record. One historian, for instance, has attempted to reconstruct the journey of a young female giraffe from Sudan to Paris in 1827 from the perspective of the animal by applying modern knowledge about giraffe psychology and physiology to contemporary writings.”

Not all animals are recorded equally in historical records, however, and Helen emphasises that some animal lives are more recoverable than others.

“The quality of information we have about animals varies significantly. Pets, for example, tend to generate the most traces because of their close relationship with humans. Zoo animals also leave behind a clearer footprint because of their exoticism, visibility and proximity to humans. Domesticated livestock and laboratory animals, however, tend to receive less attention and are more often presented in the form of statistics. So it will probably be easier to write the biography of a famous zoo animal like Jumbo the elephant than to reconstruct the life story of a sheep in Patagonia or a rat in a laboratory.”

In 1751 Pietro Longhi painted this picture of Miss Clara, a rhinoceros exhibited at the Venice Carnival. A showman wields her lost horn and a whip in front of masked members of the audience. Image: the National Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

In 1751 Pietro Longhi painted this picture of Miss Clara, a rhinoceros exhibited at the Venice Carnival. A showman wields her lost horn and a whip in front of masked members of the audience. Image: the National Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

FROM THE DEAD TO THE LIVING

After finishing her undergraduate and masters degrees at the University of Warwick, Helen decided to pursue a PhD in History.

“My PhD project looked at the study of natural history in the Spanish Empire. I was interested in the relationship between natural history and imperial power, and how it shaped local and national identities. I mainly studied animals as dead specimens in museums, though I did encounter some living creatures.”

After receiving her PhD and finalising her first book based on her thesis, Helen was searching for a new project. It was then, on the grounds of both availability and necessity, that her interest shifted from dead animals in museums to animals in zoos.

“I think my ideas were partly dictated by what I could physically do. Because I didn't at that point have funding for trips to Spain or Spanish America, I started to become quite interested in animals closer to home, in Britain. I remember seeing a photograph of two elephants walking through my home town of Stamford around 1850 as part of a travelling menagerie and wanted to find out more about interactions with exotic beasts in Victorian Britain. I began to shift from looking at collections of dead animals to collections of living ones.”

By now, Helen’s research was heavily invested in the political and philosophical aspects of the historical human–animal relationship, and the treatment of exotic animals became her focus. With this newfound interest, Helen started to investigate aspects of the Victorian zoos and travelling animal shows. This resulted in the book Exhibiting Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Empathy, Education, Entertainment.

The painting of a 19th century Menagerie by Paul Friedrich Meyerheim was meant to showcase the breadth of exotic animals available for exhibition. Photo: Paul Friedrich Meyerheim, ‘Menagerie’, 1894. Public domain.

The painting of a 19th century Menagerie by Paul Friedrich Meyerheim was meant to showcase the breadth of exotic animals available for exhibition. Photo: Paul Friedrich Meyerheim, ‘Menagerie’, 1894. Public domain.

FROM THE DEAD TO THE LIVING

After finishing her undergraduate and masters degrees at the University of Warwick, Helen decided to pursue a PhD in History.

“My PhD project looked at the study of natural history in the Spanish Empire. I was interested in the relationship between natural history and imperial power, and how it shaped local and national identities. I mainly studied animals as dead specimens in museums, though I did encounter some living creatures.”

After receiving her PhD and finalising her first book based on her thesis, Helen was searching for a new project. It was then, on the grounds of both availability and necessity, that her interest shifted from dead animals in museums to animals in zoos.

“I think my ideas were partly dictated by what I could physically do. Because I didn't at that point have funding for trips to Spain or Spanish America, I started to become quite interested in animals closer to home, in Britain. I remember seeing a photograph of two elephants walking through my home town of Stamford around 1850 as part of a travelling menagerie and wanted to find out more about interactions with exotic beasts in Victorian Britain. I began to shift from looking at collections of dead animals to collections of living ones.”

By now, Helen’s research was heavily invested in the political and philosophical aspects of the historical human–animal relationship, and the treatment of exotic animals became her focus. With this newfound interest, Helen started to investigate aspects of the Victorian zoos and travelling animal shows. This resulted in the book Exhibiting Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Empathy, Education, Entertainment.

Global animals and local commodities

After having taken up a position as lecturer at York, Helen went one step further and started to research animals as commodities. During her research the global perspective also turned unexpectedly local as she studied the British processing of alpaca fibre from Peru.

“I was intrigued to discover that Saltaire, just outside of Bradford, was the main site in Britain for spinning and weaving alpaca wool. Titus Salt’s woollen mill has now been converted into an arts and culture centre with shops and exhibitions, but if you go to Saltaire today you can still see statues of alpaca in the park, carvings of alpacas on the old schoolhouse that Salt built for his workers and even an alpaca on the badge for Saltaire cricket club.”

Helen’s work on alpacas featured in a short book on llamas. It also became part of a larger research project, Victims of Fashion: Animal Commodities in Victorian Britain, which explored the manufacture, retail and consumption of birds’ feathers, fur, ivory, animal perfumes and exotic pets. As the use of these commodities was made possible by global trade, this important aspect emerged as a central element of her research.

“I was looking at how these products were imported to Britain and how new technologies made it easier to process some of these commodities. I was also thinking about how new fashions influenced the desire to wear clothing manufactured from animals. Above all, I was interested in how ethical concerns shaped decisions about the use of animal products. One woman, on reading about the cruelty used in connection with the killing of fur seals in the Bering Sea, made up her mind never to wear a sealskin coat again, and immediately disposed of the two she already had.”

Like today, using and wearing animal products was a hot topic during the Victorian times, and the demand for animal products would go up and down in response to public campaigns. As a result, several new laws were put in place to prevent the importation of threatened species and reduce the suffering of animals exploited for fashion.

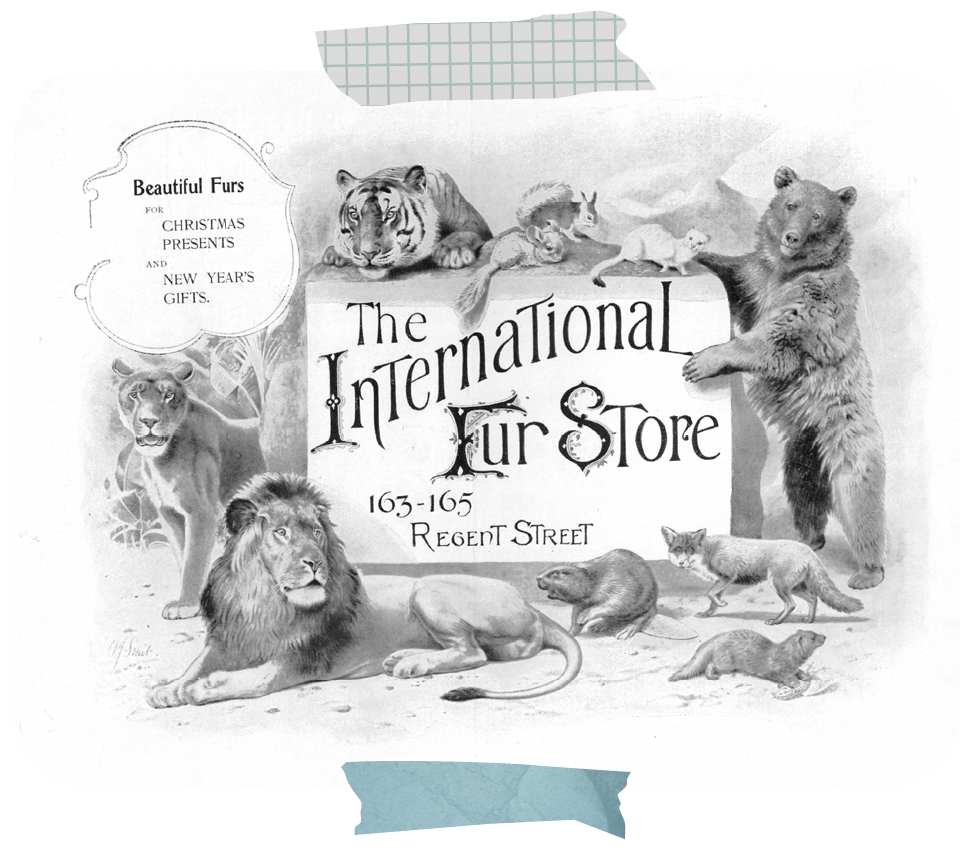

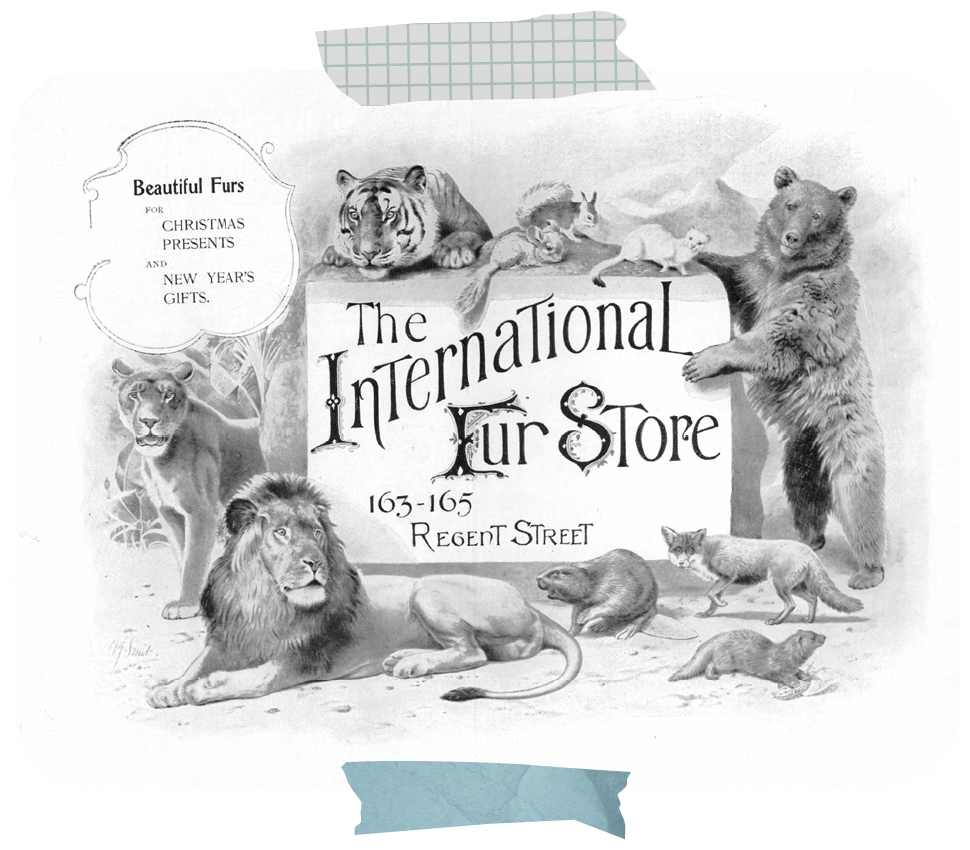

Established in 1882, the International Fur Store was located on 163-165 Regent Street in London and marketed its furs to all social classes. The store remained open until at least 1938. Photo: Helen Cowie

Established in 1882, the International Fur Store was located on 163-165 Regent Street in London and marketed its furs to all social classes. The store remained open until at least 1938. Photo: Helen Cowie

Global animals and local commodities

After having taken up a position as lecturer at York, Helen went one step further and started to research animals as commodities. During her research the global perspective also turned unexpectedly local as she studied the British processing of alpaca fibre from Peru.

“I was intrigued to discover that Saltaire, just outside of Bradford, was the main site in Britain for spinning and weaving alpaca wool. Titus Salt’s woollen mill has now been converted into an arts and culture centre with shops and exhibitions, but if you go to Saltaire today you can still see statues of alpaca in the park, carvings of alpacas on the old schoolhouse that Salt built for his workers and even an alpaca on the badge for Saltaire cricket club.”

Helen’s work on alpacas featured in a short book on llamas. It also became part of a larger research project, Victims of Fashion: Animal Commodities in Victorian Britain, which explored the manufacture, retail and consumption of birds’ feathers, fur, ivory, animal perfumes and exotic pets. As the use of these commodities was made possible by global trade, this important aspect emerged as a central element of her research.

“I was looking at how these products were imported to Britain and how new technologies made it easier to process some of these commodities. I was also thinking about how new fashions influenced the desire to wear clothing manufactured from animals. Above all, I was interested in how ethical concerns shaped decisions about the use of animal products. One woman, on reading about the cruelty used in connection with the killing of fur seals in the Bering Sea, made up her mind never to wear a sealskin coat again, and immediately disposed of the two she already had.”

Like today, using and wearing animal products was a hot topic during the Victorian times, and the demand for animal products would go up and down in response to public campaigns. As a result, several new laws were put in place to prevent the importation of threatened species and reduce the suffering of animals exploited for fashion.

Established in 1882, the International Fur Store was located on 163-165 Regent Street in London and marketed its furs to all social classes. The store remained open until at least 1938. Photo: Helen Cowie

Established in 1882, the International Fur Store was located on 163-165 Regent Street in London and marketed its furs to all social classes. The store remained open until at least 1938. Photo: Helen Cowie

"Animal cruelty hasn’t disappeared, but it has certainly become less visible. If I were to walk through the streets of York in the 17th century, I might have seen bears being baited for entertainment, sheep being driven to market or pigs being butchered for their meat. I wouldn’t see that today, but that doesn’t mean animals aren’t still being mistreated."

"Animal cruelty hasn’t disappeared, but it has certainly become less visible. If I were to walk through the streets of York in the 17th century, I might have seen bears being baited for entertainment, sheep being driven to market or pigs being butchered for their meat. I wouldn’t see that today, but that doesn’t mean animals aren’t still being mistreated."

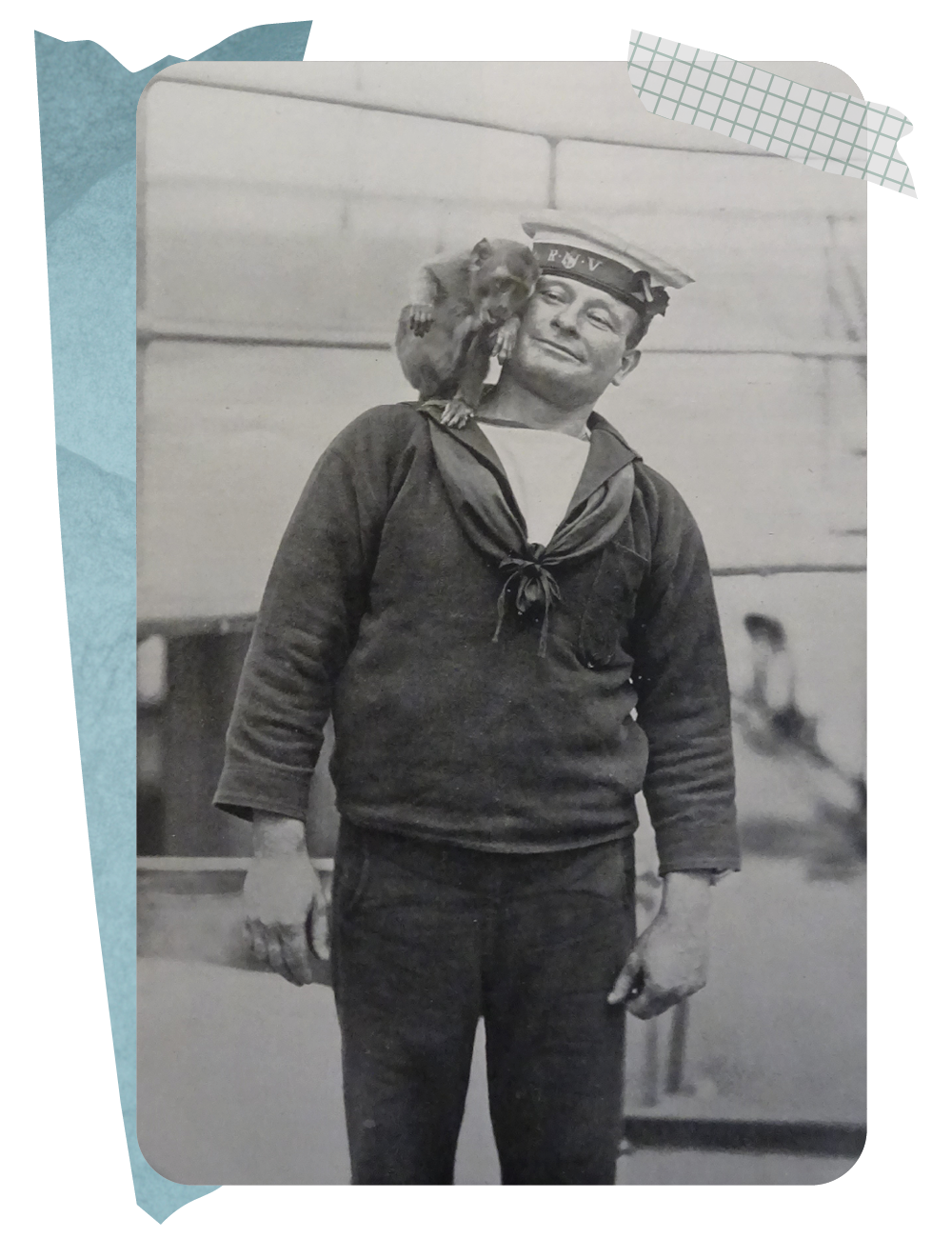

Animals and humans today

Helen’s latest book, Animals in World History, takes on an even broader perspective. Intended as an introduction to the field for students and people who don't yet know much about animal history, the book highlights different aspects of the human–animal relationship from the Palaeolithic to the present day.

“Animals in World History tells the story of the human–animal relationships over time and across different geographies. It talks about how animals have shaped human history by, for example, facilitating trade, ploughing fields or as companions. It also explores how humans have impacted the overall biodiversity of the planet, driving some species to extinction while letting others colonise new continents.”

In the book, Helen also shines a light on modern day human–animal relationships. By asking why some treatments of animals are considered acceptable but not others, she raises complex moral questions. In 1960s America, for example, the use of baboons as crash test dummies generated outrage, but the use of the same animals in a medical testing facility provoked little comment.

“Why was using baboons for one purpose better than another? Was it the level of suffering that mattered most, or the perceived value of the research?”

With modern life came new relationships. In earlier periods, people lived more closely with animals, and were more likely to see frequent everyday human–animal interactions. Today, by contrast, people enjoy increasingly intimate relationships with a few privileged species such as cats and dogs, but have relatively little contact with wild or farmed animals.

“Animal cruelty hasn’t disappeared, but it has certainly become less visible. If I were to walk through the streets of York in the 17th century, I might have seen bears being baited for entertainment, sheep being driven to market or pigs being butchered for their meat. I wouldn’t see that today, but that doesn’t mean animals aren’t still being mistreated.”

While animal protections have increased since the 19th century, therefore, Helen regards the question of whether humans are kinder to animals today as a complex one.

“I would say, ultimately, we're not kinder, but I think it’s quite complicated. We certainly know more about animals’ abilities. We understand that chimpanzees can use tools, whales communicate via sophisticated clicks and elephants can recognise themselves in the mirror. We also have laws in place to protect some animals from abuse. But at the same time we subject more farmed animals to inhumane conditions than ever before through intensive agriculture and threaten the continued existence of wild animals with poaching, pollution and habitat destruction.”

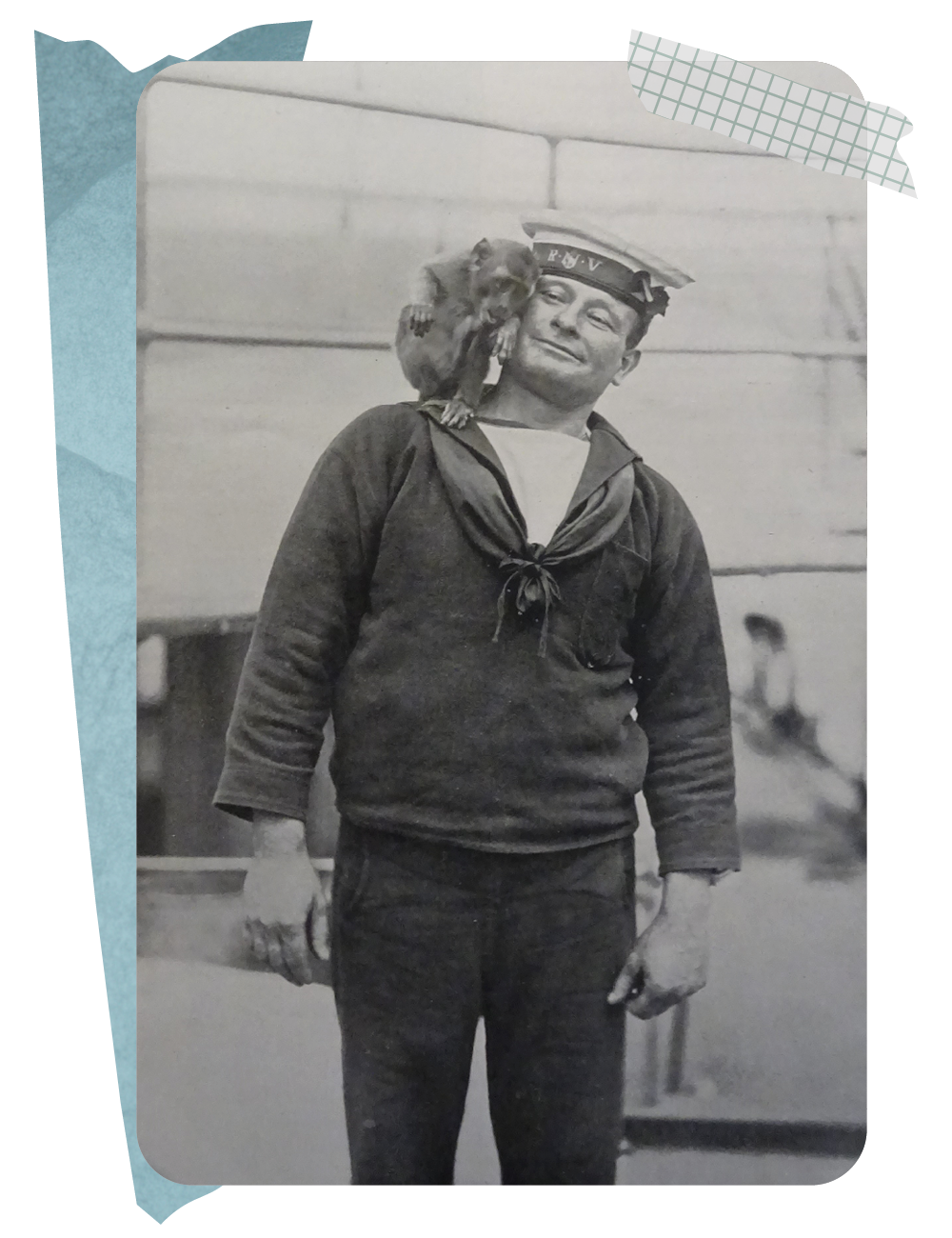

Taken from the 1906 book series The Animal World, the picture shows a sailor and a capuchin monkey on board the Royal Navy volunteer ship Buzzard in Blackfriars, London. Photographer unknown.

Taken from the 1906 book series The Animal World, the picture shows a sailor and a capuchin monkey on board the Royal Navy volunteer ship Buzzard in Blackfriars, London. Photographer unknown.

Animals and humans today

Helen’s latest book, Animals in World History, takes on an even broader perspective. Intended as an introduction to the field for students and people who don't yet know much about animal history, the book highlights different aspects of the human–animal relationship from the Palaeolithic to the present day.

“Animals in World History tells the story of the human–animal relationships over time and across different geographies. It talks about how animals have shaped human history by, for example, facilitating trade, ploughing fields or as companions. It also explores how humans have impacted the overall biodiversity of the planet, driving some species to extinction while letting others colonise new continents.”

In the book, Helen also shines a light on modern day human–animal relationships. By asking why some treatments of animals are considered acceptable but not others, she raises complex moral questions. In 1960s America, for example, the use of baboons as crash test dummies generated outrage, but the use of the same animals in a medical testing facility provoked little comment.

“Why was using baboons for one purpose better than another? Was it the level of suffering that mattered most, or the perceived value of the research?”

With modern life came new relationships. In earlier periods, people lived more closely with animals, and were more likely to see frequent everyday human–animal interactions. Today, by contrast, people enjoy increasingly intimate relationships with a few privileged species such as cats and dogs, but have relatively little contact with wild or farmed animals.

“Animal cruelty hasn’t disappeared, but it has certainly become less visible. If I were to walk through the streets of York in the 17th century, I might have seen bears being baited for entertainment, sheep being driven to market or pigs being butchered for their meat. I wouldn’t see that today, but that doesn’t mean animals aren’t still being mistreated.”

While animal protections have increased since the 19th century, therefore, Helen regards the question of whether humans are kinder to animals today as a complex one.

“I would say, ultimately, we're not kinder, but I think it’s quite complicated. We certainly know more about animals’ abilities. We understand that chimpanzees can use tools, whales communicate via sophisticated clicks and elephants can recognise themselves in the mirror. We also have laws in place to protect some animals from abuse. But at the same time we subject more farmed animals to inhumane conditions than ever before through intensive agriculture and threaten the continued existence of wild animals with poaching, pollution and habitat destruction.”

Taken from the 1906 book series The Animal World, the picture shows a sailor and a capuchin monkey on board the Royal Navy volunteer ship Buzzard in Blackfriars, London. Photographer unknown.

Taken from the 1906 book series The Animal World, the picture shows a sailor and a capuchin monkey on board the Royal Navy volunteer ship Buzzard in Blackfriars, London. Photographer unknown.

THE STORIES FOR TOMORROW

With the modern human–animal relationship in mind, Helen thinks the history of animals is a growing field, which will expand in future to cover new places and species.

“In the future I expect we will see more histories of previously neglected species, such as rats, insects and reptiles, and more focus on interspecies relationships.”

While interactions between animals and humans have always been both positive and negative, Helen believes that we should tell the stories unfiltered with the aim of shining a light on both present and future stories.

“It is important to include animals in our histories and to recognise them as historical actors. Writing the history of animals also helps us understand how we treat them today, and how we want to treat them in the future.”

THE STORIES FOR TOMORROW

With the modern human–animal relationship in mind, Helen thinks the history of animals is a growing field, which will expand in future to cover new places and species.

“In the future I expect we will see more histories of previously neglected species, such as rats, insects and reptiles, and more focus on interspecies relationships.”

While interactions between animals and humans have always been both positive and negative, Helen believes that we should tell the stories unfiltered with the aim of shining a light on both present and future stories.

“It is important to include animals in our histories and to recognise them as historical actors. Writing the history of animals also helps us understand how we treat them today, and how we want to treat them in the future.”

Helen Cowie is Professor of History in the Department of History at the University of York.

Her latest book Animals in World History is available through Routledge.

Helen Cowie is Professor of History in the Department of History at the University of York.

Her latest book Animals in World History is available through Routledge.