YORK RESEARCH JOURNEYS

Professor Sara de Jong

On 15 August 2021, the eyes of the world turned to the city of Kabul. A months-long offensive by Taliban forces had suddenly succeeded in capturing the capital city, overthrowing the government and regaining the political control wrestled from them by an international military coalition during the US-Afghanistan war.

It was a swift and traumatic end to Britain’s twenty-year campaign in Afghanistan, a campaign in which NATO militaries, including the UK, enlisted thousands of Afghan civilians known as Locally Employed Staff, to help in the fight against the Taliban. As ex-employees and allies of the evacuating armies, these individuals became easily identifiable enemies of the Taliban regime and were in significant danger.

In mid-August, thousands hurried to the Kabul airports in hope of emergency evacuation. By the end of the month, approximately 114,000 people had been evacuated by the US and NATO forces in planes packed with desperate, fleeing people.

Operation Pitting - the British military evacuation operation - evacuated 15,000 people (including British nationals) on more than 100 RAF flights from Kabul to the UK, in the largest British evacuation since the Second World War.

This included 495 former local Afghan staff who had worked for the Ministry of Defence, 242 who had worked for the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and 43 who had worked for the British Council. They were evacuated along with their immediate families - the youngest evacuee on the British military planes was only one day old.

An Afghan man hands his child to a British Paratrooper at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 26, 2021. Image from the U.S. Central Command Public Affairs.

POLITICAL GO-BETWEENS

Four years earlier in 2017, Professor Sara de Jong had started a research project on the claims to protection and rights by Afghan and Iraqi military interpreters and other locally employed civilians assisting British and other Western troops.

She explains: “Back then, few people were interested in the situation surrounding Afghan ex-interpreters and locally employed civilians’ rights and lives. It was a niche area of study, and I didn’t know many people interested in the topic. Things changed, of course.”

Professor de Jong’s research field is international relations, and her specialism is in working with a range of individuals affected by the broader international political landscape.

Dr Sara de Jong in her office at the University of York. On display are images from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There.

“People often think of politics as something that happens between countries, institutions or parties and perhaps lose sight of the way it affects people personally. A lot of the people I work with are displaced or have been affected by war which is most certainly an issue of international relations.”

This particular research idea came to her while she was preparing a lecture and was looking for good contemporary examples of ‘political go-betweens’ - individuals who mediate between two different people groups, governments or companies.

Professor de Jong ultimately found an example for her lecture in The Interpreters - a documentary following an Iraqi man once employed as a translator for American soldiers during the US occupation in Iraq. The film documents how as a result of his work, his life becomes endangered and he flees his home country.

She said: “I’ve been interested in studying political go-betweens for a long time, since my postdoc at the University of Vienna in fact. They have played significant roles in international politics and world history, but it's not a commonly studied area of research. Some of the names of historical mediators are familiar to us, Pocahontas is one example, but others remain completely invisible.

“Interpreters are really good examples of these figures. On the one hand they can have a lot of power, but they are also put in a very precarious position. They may be working with the occupying army and therefore considered a traitor by some of their own community. Some have their lives turned upside-down, face being separated from their families, or have to start a new life in an unknown country.”

After her lectures on political go-betweens she started to think about the UK’s and NATO’s military involvement in Afghanistan, which began in 2001 after the events of 9/11 and, at the time, was still ongoing. She started shaping her ideas and began the project shortly after.

She has since conducted more than 80 interviews with Afghan interpreters and advocates in the UK, the US, Canada, Germany, France and the Netherlands.

RESEARCH REALITIES

Although it began life as a fairly niche area of research, Professor de Jong’s work has taken on a new, urgent scope since August 2021. Thousands of Locally Employed Staff and their families are now refugees in the UK, trying to find stability in their upended lives.

Furthermore, in March 2023 the UK Ministry of Defence estimated more than 4,000 Locally Employed Staff and their families who are eligible for relocation are still in Afghanistan. Approximately 1,000 of those were left behind at the sudden end of Operation Pitting. Many of these people are making attempts to leave and are in great need of assistance and support.

Professor de Jong’s research in this area has become a vital part of representing the voices of these individuals in British politics.

As well as regularly providing informed comments in the national press, she has provided oral and written evidence to the UK Parliament Defence Select Committee on two occasions - at their hearings on Afghan locally engaged civilians (November 2017) and the withdrawal from Afghanistan (November 2021).

Additionally, in August 2021 while the situation was unfolding in Afghanistan, Professor de Jong was invited to provide oral evidence to the Dutch Parliament Defence Committee roundtable on the security situation in Afghanistan.

She hopes that her participation in these spaces can bring real-world change. When asked what she would like people to say about her work she is very specific:

“I hope my work puts pressure on western governments to make improvements to refugee resettlement policies, limiting trauma and distress for displaced people, get justice for former Afghan employees and allow them to start a new, integrated life in the country that employed them.”

Her involvement in this area of research has also led to her co-founding of the Sulha Alliance, an organisation that campaigns for the rights of Afghan former interpreters and other Locally Employed Civilians who have worked with the British Armed Forces.

REPRESENTING HIDDEN VOICES

The public interest in the Afghan political landscape in 2021 provided Professor de Jong with an opportunity to adapt her research into a public-facing artistic endeavour.

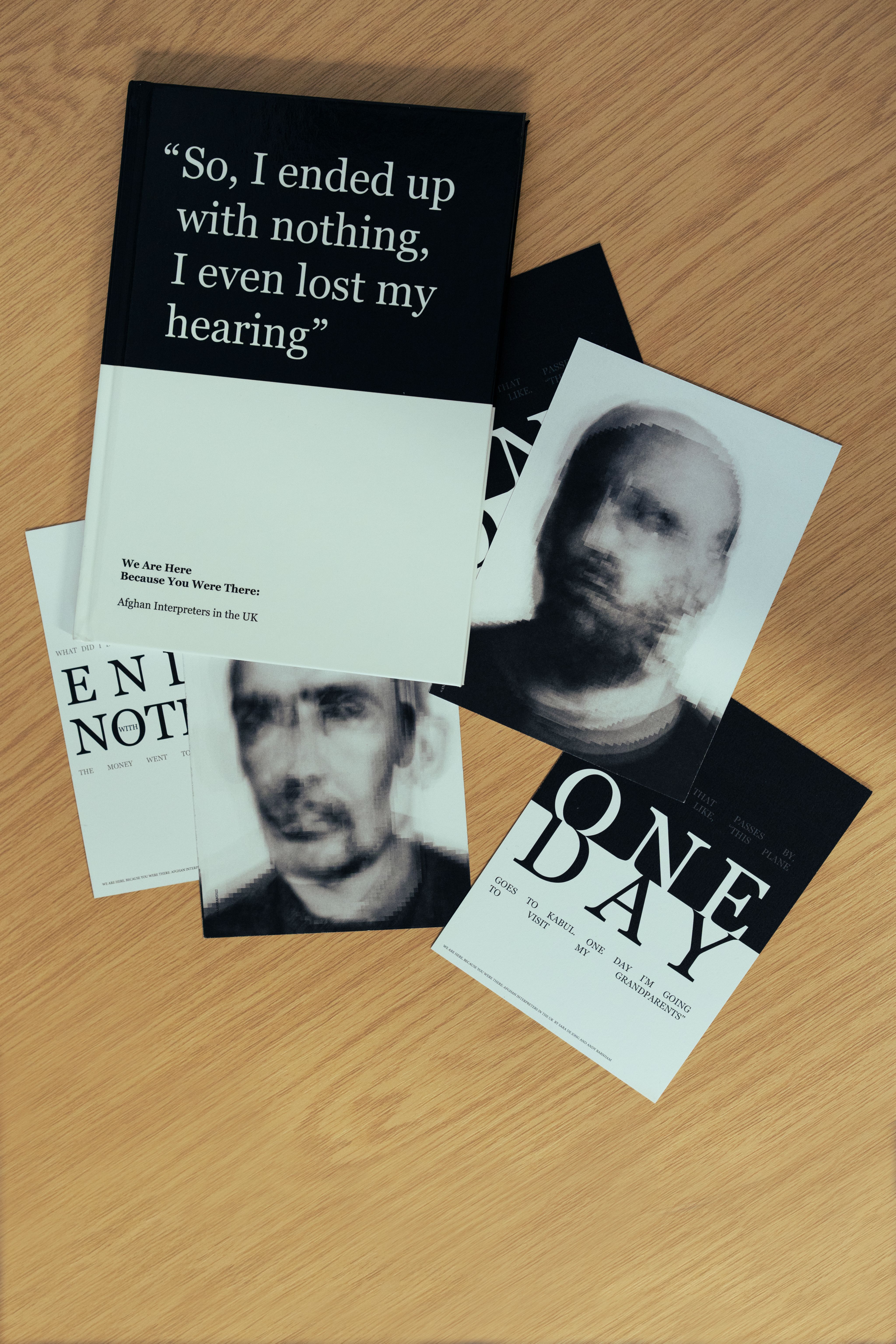

Working with the photographer and army veteran Andy Barnham, Professor de Jong’s interviews formed part of an art exhibition titled We Are Here, Because You Were There.

The exhibition toured the UK from October 2022 to March 2023 with stints in Glasgow, Cambridge, London and Cardiff. It can now be experienced virtually online.

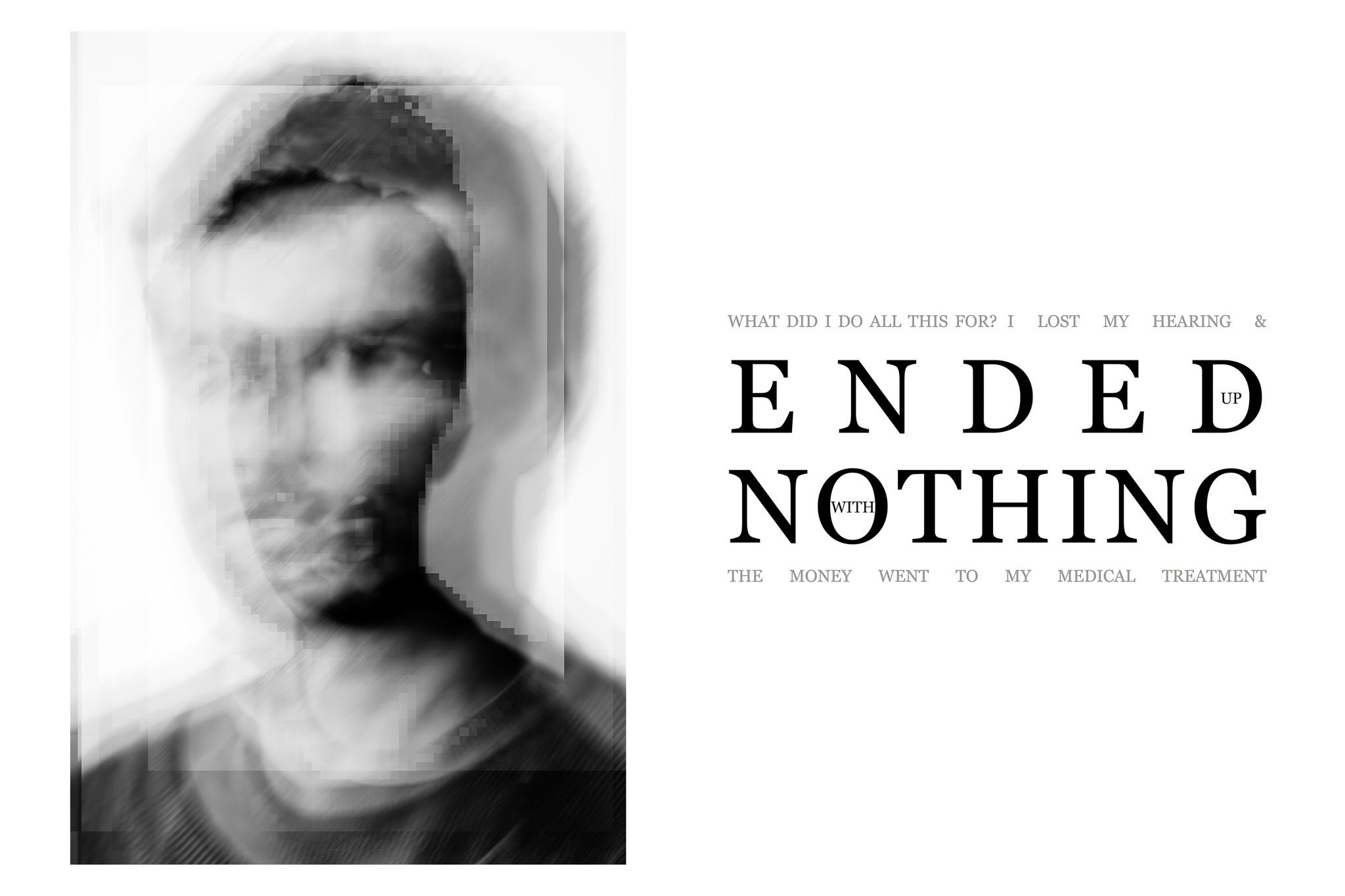

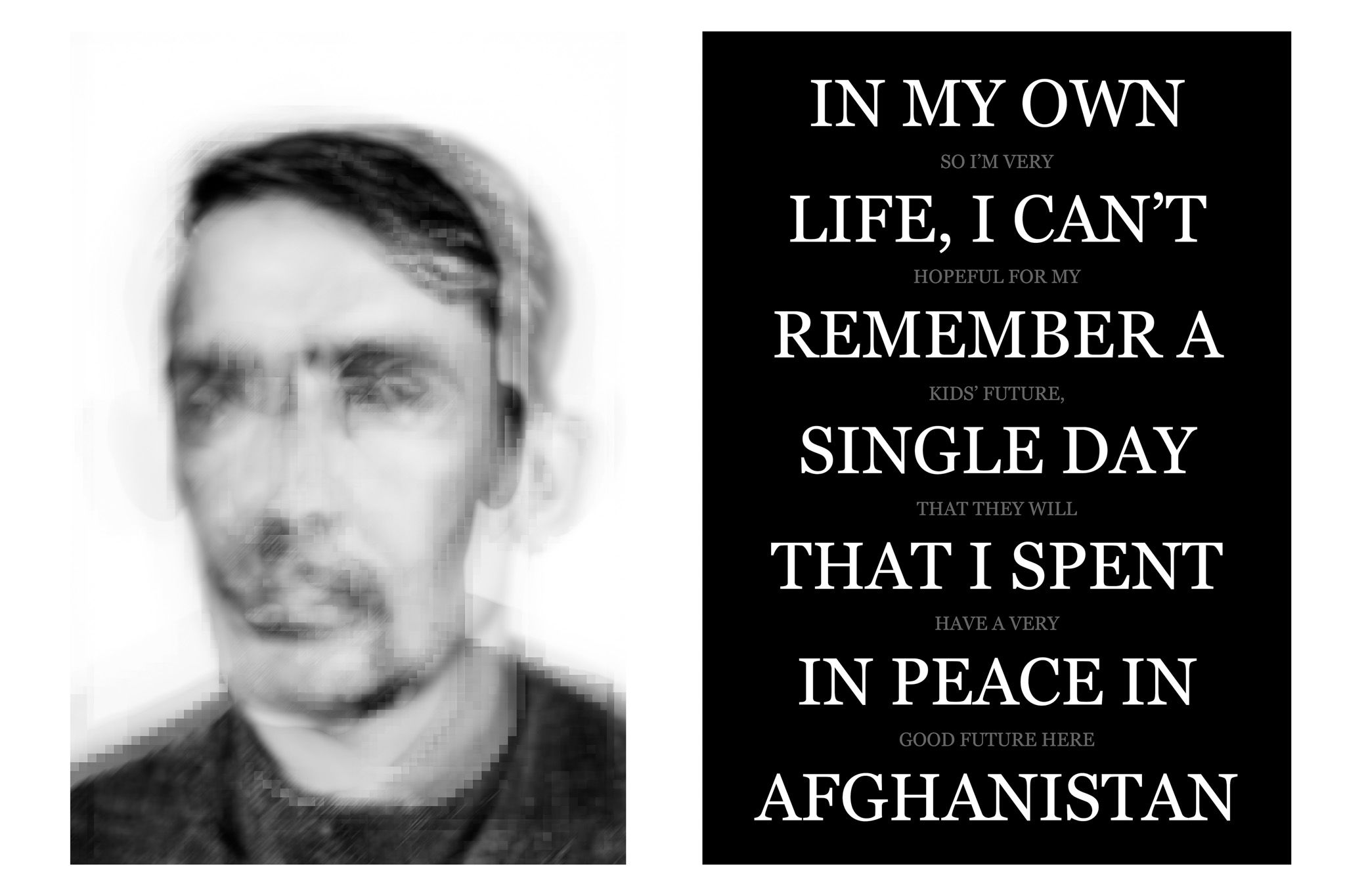

Barnham attended several interviews with Professor de Jong, taking photos of the interviewees which were blended and pixelated to create anonymised portraits.

The anonymisation of these individuals is vitally important. Although the subjects of Barnham's photographs have been able to flee Afghanistan with their spouses and children, they have left behind parents and siblings, many of whom are now in hiding. These family members face a very real threat to life if it is discovered they are related to interpreters who worked with the US or their NATO allies.

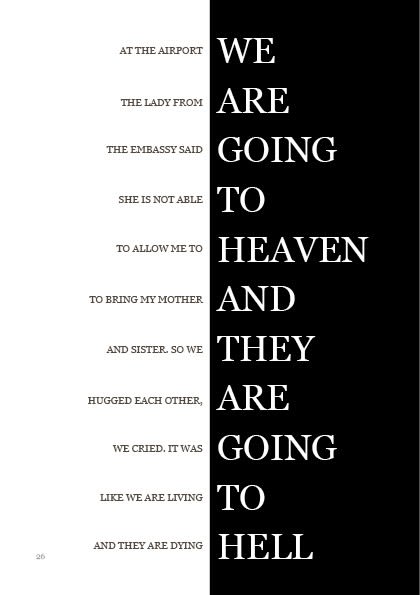

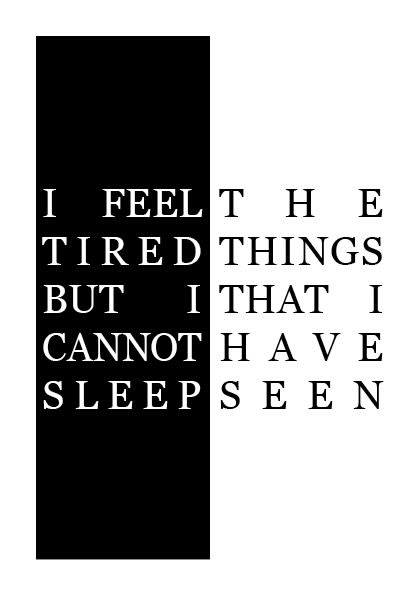

Extracts from the 14 interviews were turned into accompanying graphics and the resulting art pieces are a powerfully articulated snapshot of the lives of Afghan interpreters, their sacrifices, trauma and pain.

The images explore the difficulties these people, now refugees, have faced in and since their employment with the British Armed Forces.

Professor de Jong said: “These interviews require emotional labour on both sides. Sharing their experience as patrol interpreters and their evacuation often touches on trauma and, understandably, this can be quite emotional. It’s hard seeing someone break down in tears and not be able to offer them real comfort beyond informing them about their rights and available support. Some participants did feel relieved to have someone listen to their story and said they would finally be able to sleep that night.”

She also mentioned a story about an interviewee who changes into his Afghan clothing for the photo: “He said it was his only set of Afghan clothes, and I realised this was what he was wearing as he was evacuated, he wasn’t able to bring anything else with him and the garment had been witness to horrific airport scenes.”

The exhibition pieces certainly do not shy away from the very real dangers these individuals have faced. One particularly stark quote reads: “The Taliban, the enemy thought interpreters are the tongue and eyes of the British forces. They announced ‘You should kill the interpreters first because they are showing the soldiers the way.’”

They announced "You should kill the interpreters first because they are showing the soldiers the way"

They announced "You should kill the interpreters first because they are showing the soldiers the way"

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Photography and design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

An image from the exhibition We Are Here, Because You Were There. Photography and design by Andy Barnham, quote by Dr Sara de Jong.

It’s the lived realities that Professor de Jong says she has always been keen to highlight in her research: “When the people I interview read my work, I hope they say that it has done justice to their stories, that they recognise themselves in my account.”

She’s been able to stay in touch with some people she’s encountered through her research, and she mentions that’s a real highlight of the work.

Furthermore, PhD students are now applying with thesis proposals relating to Professor de Jong’s work with Afghan interpreters. What was once a small, unpopular topic in the field of politics has now been engaged with by political actors, academic researchers, students and members of the public who’ve attended the exhibition.

Professor de Jong also says that being aware of those facing injustices has changed her, too. It’s repeatedly spurred her into action, whether that is volunteering at a women’s project as a PhD student, to volunteering as a befriender to women in detention centres, to starting the Sulha Alliance.

It’s also changed the way she sees the world, “A lot of people I work with are individuals trying to help in deeply complicated political situations and the effects on their own lives can be heartbreaking. Listening to so many people’s stories in my research interviews, I find myself far less quick to judge others. I am aware that people passing me on the street each have a very complex story behind them.”

"Listening to so many people’s stories in my research interviews, I find myself far less quick to judge others."

"Listening to so many people’s stories in my research interviews, I find myself far less quick to judge others."

FIND OUT MORE

WE ARE HERE, BECAUSE YOU WERE THERE

Experience the virtual exhibition

View the image catalogue online

The University of York is a University of Sanctuary. We welcome those who are displaced and seek to be a safe place for refugees, asylum seekers and other people who have been forced to migrate.

In response to the Afghanistan crisis in 2021, we were able to act quickly to support six students fleeing the country. Find out how you can help us support students with asylum-seeking status.